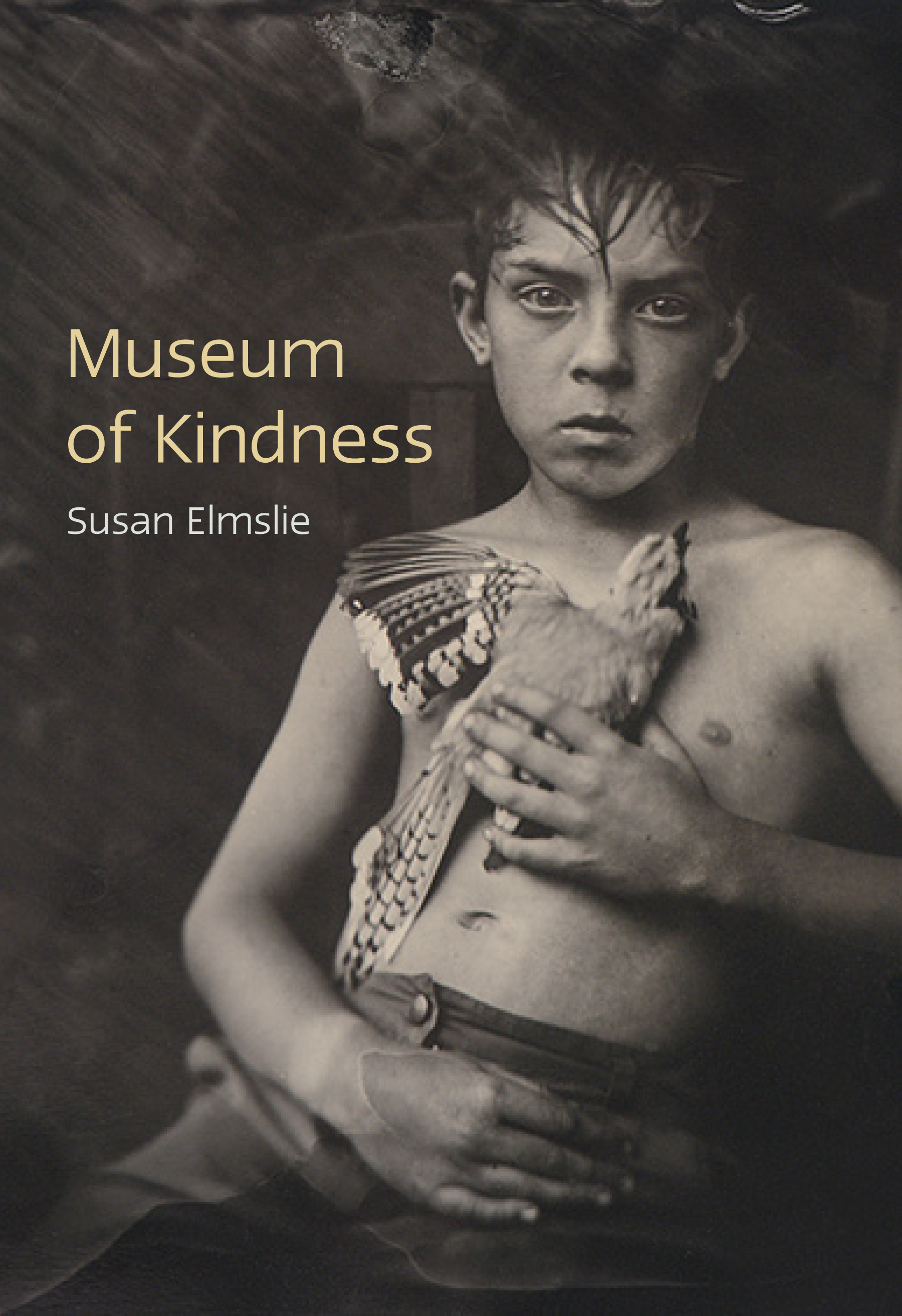

Susan Elmslie. Museum of Kindness. Brick Books.$20.00, 113 pp., ISBN: 978-1771314671

A Review of Susan Elmslie's Museum of Kindness

Review by Shazia Hafiz Ramji

Susan Elmslie’s second book of poetry, Museum of Kindness, takes up the task of making meaning out of trauma. As in her first award-winning book of poems, I, Nadja, and Other Poems, Elmslie illuminates the lives of girls and women in slice-of-life poems that find their way through love and violence in all its forms.

In four sections, the speaker moves through instances of violence in childhood, the responsibility of a teacher and parent during a school shooting, and her newborn son’s disability. In the opening section, “Material,” the speaker confesses to using pain as the material for poems. The last poem of the same name admits: “One of the perks of pain. Gifted / with an endless supply of material, / redemption only a roundel away.” Careful line breaks and a tweaking of the registers of language place Elmslie’s poems on the line between sincerity and irony. The speaker at once acknowledges the paradox of the “gifted” as being a “perk,” a phrase borrowed from the language of marketing and advertising, which conveys an awareness that these poems capitalize on pain. However, Elmslie’s poems don’t settle on self-awareness, cynical irony, or effusive sincerity. Instead, they move into the core of this pain by way of first-person narration written with an ease and precision that place the reader in the role of a confidant.

Consider the second section, “Trigger Warning,” in which the speaker is a teacher at Dawson College, where a school shooting occurs. In the poem that opens this section, “School Shooting,” the speaker meets the eyes of a little girl between gunshots and beholds her daughter, coming to the realization that she might die and leave her daughter. The speaker feels surprisingly at peace: “[…] I could go / true as a tree felled by lightning.” The poem seemingly ends a few lines later, but the next page offers a coda:

I can tell you there is a static silence

between reports of a gun; bullets

pierce drywall; we were too afraid to move

a filing cabinet to block the door;

when the smooth-jawed SWAT officer

ordered me to hold it open for my students

then swung around to cover my back I felt

his core hot and trembling through Kevlar. (18)

Elmslie’s intimate tone creates the space of silence in these descriptive lines as the mind moves to grasp the officer’s trembling body. Her specificity and plain-spokenness make these poems buoyant in their darkness.

This coupling of levity and gravitas returns us to the personal in the third and longest section of the book, “Threshold,” in which Elmslie articulates the difficulty of accepting her newborn son’s disability and the various labels imposed on him. In “Broken Baby Blues,” Elmslie borrows the rhythm and rhyme of blues songs that are simultaneously playful and dark:

Can I say it to myself, I’ve got the broken baby blues?

Can I say it to the wind, I’ve got the broken baby blues?

Listen to me sister, walk a mile in my shoes.

[…]

Ain’t no mama nowhere safe from broken baby blues.

No daddy—God in heaven!—hasn’t paid his dues.

Lord God save my baby from the broken mama blues. (59)

The turn in the lines that close the poem refocuses the subject from the child to the mother and father, creating a surprise and a rush of empathy, which convey a depth of love that is often difficult to articulate. Borrowing from the blues genre speaks to Elmslie’s perceptive grasp of what poems can do as they inhabit thresholds to create possibility.

The strongest poems in this collection embody beauty and pain while also being plainspoken and musical, and this sensibility ascends throughout the collection. In the poem that shares the title of the book and last section, “Museum of Kindness,” the speaker thinks of the objects, drugs, and institutions that could potentially be included in a Museum of Kindness. She reflects on the hospitality of her friends and their invitation to celebrate Christmas, and she regrets not sending them a thank you card every year:

8.

[…]

How can it be that, every year,

I fail to send a thank you card.

9.

There’d be a wing devoted to the best

intentions.

I think if it existed, we’d go. (102)

Once again, Elmslie masters the turn by refocusing the poem and playfully twisting readers’ expectations. One might think that intentions to send thank you cards might be enough, but the poem anticipates this expectation. It makes a leap to consider the space of this intention by returning the poem to the subject of the guests, renewing the sense of hospitality that began the poem.

Museum of Kindness is written with an impulse of generosity that guides these poems to inhabit and understand complex lives. In Elmslie’s hands, the quotidian is transformed into quiet and piercing moments of acceptance. These poems are candid and musical, transforming pain into beauty in the inexplicable way of resilience.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji was a finalist for the 2018 Alberta Magazine Awards and received the 2017 Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry. Her writing has recently appeared in Hamilton Arts & Letters, Quill & Quire, and Metatron’s ALPHA. Her debut book of poetry, Port of Being, is forthcoming from Invisible Press in fall 2018.