Unveiling the Layers: Puneet Dutt Reviews Chuqiao Yang’s The Last to the Party

June 30, 2024

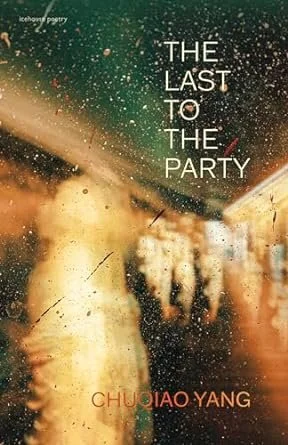

The Last to the Party. Chuqiao Yang. icehouse poetry. $19.95, 108 pp., ISBN: 9781773103334

Many in the Canadian literary community have awaited the publication of Chuqiao Yang’s first full-length poetry collection.

Yang won the prestigious bpNichol Chapbook Award for Reunions in the Year of the Sheep (London ON: Baseline Press, 2017) and continues to contribute significantly to the Canadian literary community. Through her past work at Canthius magazine and her current role as Poetry Editor at The Fiddlehead, she has built a strong name for herself as a writer to watch.

In this debut, Yang invites readers on a journey through the intricacies of emotions, experiences, and the changing landscapes of life. Told from the perspective of an “educated young Canadian” wanting a “wild pursuit of a life,” with a delicate balance of introspection, observation, and wry humour, Yang explores themes of love, loss, identity, and resilience. She weaves together lyrical verses that resonate long after the last pages have been turned.

Although some poems from her chapbook make an appearance in this full collection, readers will read them afresh, as they are placed with new poems in four sections.

In the opening poem, “8th Street”, the narrator lays bare a deeply felt “half a self”, with a mature and evolving voice in a state of wonder. This voice is self-aware of the one half, “unforgiving, cruel, greedy”, while the other half remains in flux, “I wanted to look like her, found fault / in my mother for saying / I would.”

Despite vacillations, the voices in many of Yang’s poems seem to be filled with hope. In “The Party” the narrator speaks in a calm and self-assured voice to herself: “I tell her better days / are coming. Because they’ve come, and keep on coming…” and in another poem, "The Night I Left Home", we hear this confidence again: “But my dark, dog-bit mouth and its scars: / thinning, shifting, promising.” And then in “Eve”, the narrator seems eager to embrace a future. “So I tap them awake because there’s a party / to be had, and a future to greet.”

One could argue, as Gregory Orr wrote in Poetry as Survival, that some poems act as “momentary stays against confusion…[and] articulate with eloquent simplicity a…power to lift moments of clarified drama out of the ceaseless, discombobulating flow of experience and, by doing so, to restabilize the self.” Yang’s narrator achieves this “restabilization” by longing for a stability for days that are yet to come.

In “The Party” the narrator speaks wistfully of want: “Sometimes I imagine / meeting my future children / as strangers at some party.” And although the narrator’s voice appears to seek stability, many poems are written in a style of cinematic flashbacks told from a vast sweeping landscape of past and present occurrences, and across many geographical locations.

For example, in the poem “Raspberries”, the narrator eloquently describes this want: "I hungered, I longed, / I balked at the thought of a life without the full, / brute strength of desire." And we hear this wanting again in “Art Therapy with a Squirrel”: “One day, I too will embrace / the hunger in me, even if / this untethered, boundless / greenery buds into nothing.”

Furthermore, with a title like The Last to the Party readers expect, and are given, musical references in the text. And the book delivers with nods to Michael Bolton playing in a taxi, Tina Turner songs, scenes of dancing, and of course—parties.

There are also many powerful poems that seem as if they arrived perfectly carved, such as “The Geologist”. You cannot fault this poem. It is a masterful stroke for a poet who is just getting started and is a rare feat to achieve in first books.

The poem, uses a technique called ‘braiding’. It weaves together complex scenes that are working apart at first, only to come together in the end. This is not an easy thing to achieve, and a lesser poet might try this technique, but quickly lose the reader’s attention.

But Yang succeeds in this ‘braiding’ technique through the following ways: One, by using a repetition of words; the narrator emphasizes the desire for exploration and curiosity, but also brings the reader back to a central question. Two, the narrator strengthens the poem using robust imagery, such as the father’s voice crackling through the telephone. This provides a moment for the reader to pause briefly and visualize the scene.

There are a few additional techniques that add depth to this poem. The narrator’s use of the moon as a metaphor allows readers to view it as a stand in for life's challenges and the different ways people approach them. Another method used is the poem’s symbolism that comes from the addition of rock formations. It works well alongside the narrative of a strong father offering sturdy guidance and support.

What adds further layers in this poem is the emotional resonance between father and daughter. Instances of alliteration add musicality and rhythm to the poem, such as "broomsticked heart hungry black" and "broomsticked heart hungry blue”. And finally, the juxtaposition between the practicality of survival that the father advises to the narrator, and the pursuit of passion that the narrator feels an urge to pursue is what gives the poem its tension.

In another one of my personal favorites, “8th Street”, the young narrator grapples with wanting to attend a concert, “belting Bon Jovi,” and trying to shake off overprotective parents to finally begin “playing at last / the debut part / of properly unsafe, / sixteen…”. At the end, there is a gut punch for the reader. I won’t spoil it, but I will say this: one of the toughest things to achieve in great lyric poems is the turn—and what a turn “8th Street” contains.

What sets Yang’s poetry apart is the narrator’s distinctive voice: intelligent and colloquial, cosmopolitan in its awareness of both Canadian small towns and international cities, and blending it all in with conversational dialogue and humor. And then, there’s that powerful thing that happens with the ambiguity. Take this line from “Art Therapy with a Squirrel”:

“…my ancestors’ graves thirst for revenge./ But homage is a tedious phonebook of names.” And here, in “The Road Home”: “Some dude on a fixed gear / asks me my race, / and I say easy, Slow. / Lost in translation, / I am bleeding in Shanxi, / entitled to everything, / cut arm, cat gone, / neither here nor there / but breathing.”

Many of the poems are long-armed poems, a term used by poet Ellen Bass to describe a technique in which a poem “reaches out and sweeps disparate, unexpected things into its net and yet the elements have enough magnetic attraction, enough resonance that the poem holds together” helping to create the necessary tension. As Mark Doty writes: “The more the yoked things do not have in common, the greater the tension.”

Take these lines for example, from the poem “Family Tree” that sweep and grab so much eloquence and beauty, with grace and simplicity, while also speaking of diasporic experience:

“As my father searches my hands to forgive my brother who / wanders, / as I honour our family by rewriting the songs of our history, / as I go to a school-ground hill in search of fallen water, / as I place the crow’s beak in my slipping mouth.”

Additionally, many of the other poems in the collection have well-rendered imagery, movement, and surprise. But the attention given to the sound of the words layer many of the poems with an added beauty. In “8th Street” the “aw” sounds compliment the subject matter with their own musicality, “away”, “Jaw”, “hawk”, “gawked”, “lawn”. In “Trisha and the Wonder Years” there is this marvelous dessert: “ate aged couch-cushion chocolates”.

Another strength of this book is that it’s full of sensuous details. Take this gem in “The Night I Left Home”: “there were gold leaves / beating in the air, midribs shaped like the scars / on my dog-bit lips, two thin silver lines still healing.” In the poem “Nanjing”, this jewel: “how the sun shivered / in the Qinhuai River like a golden bangle.” And in the poem, “The Reminder”: “Each day is a bird / flicking its wings dry in a field.” “The Road Home” also delights with this: “An old friend once gave me a monarch’s wing. / How closely it resembled an orange sail.” And in the poem “Raspberries” is one of my favorite images: “wild raspberries grew, wiry and sour… / hairy rubies into our hands”.

These poems also illustrate a painful experience of diasporic existence, such as in “The Night I Left Home”: “shards of my family’s gifts slivered into me.” In "The Road Home" “as I move again / out the door / of one country / and into another”. In the poem "Art Therapy with a Squirrel": “Meanwhile my ancestors’ graves thirst for revenge.”

In “Lost in Translation”, the narrator says, “I recall falling to my knees on the mountain of the dead, where my uncles, my aunts, and my ancestors wept, as we poured spirits over Lao Yei’s tomb, burned incense and drawings, we were mourning but I kept my spirits up.”

Whether delving into the complexities of romantic love or the bonds of family, Yang’s words possess a raw honesty that pierces through the surface layers of emotion. Self and world-aware, wrestling with ideas of privilege and luck, the narrator is attuned: “This life is only / possible because of good timing.” The poems are told with wry humour through a narrator that stands ready to respond to cliches: “I rush out of the floorboards of my life / to shepherd clichés back to their origins.”

In "How Do Poets Choose a Collection’s Final Poem?", Sarah Blake writes: “The final poem has a large task—it has to make the book feel finished. It will, by its position, speak to every other poem in the book. It will inevitably turn the reader somewhere; the author decides where that will be. And the final poem will beg feelings of satisfaction for the reader. It’s a lot to ask of a single poem.”

Yang’s last stanza in the last poem of the book, “The Road Home”, delivers by turning the reader forward on a positive and hopeful note: “And my future is bright, and my future is good”.

In conclusion, "The Last to the Party" is a remarkable debut, both captivating and thought-provoking. Yang has a remarkable ability to capture the complexities of the human experience with great insight. With profound themes, and beauty in language, this collection will resonate with many readers.

Puneet Dutt’s ‘The Better Monsters’ was a Finalist for the Trillium Book Award for Poetry and was Shortlisted for the Raymond Souster Award. Her most recent chapbook was Longlisted for the 2020 Frontier Digital Chapbook Contest, selected by Carl Phillips. Dutt lives in Markham with her partner and two kids.