The Spell of the Mundane: Vinh Nguyen on Anuja Varghese's Chrysalis

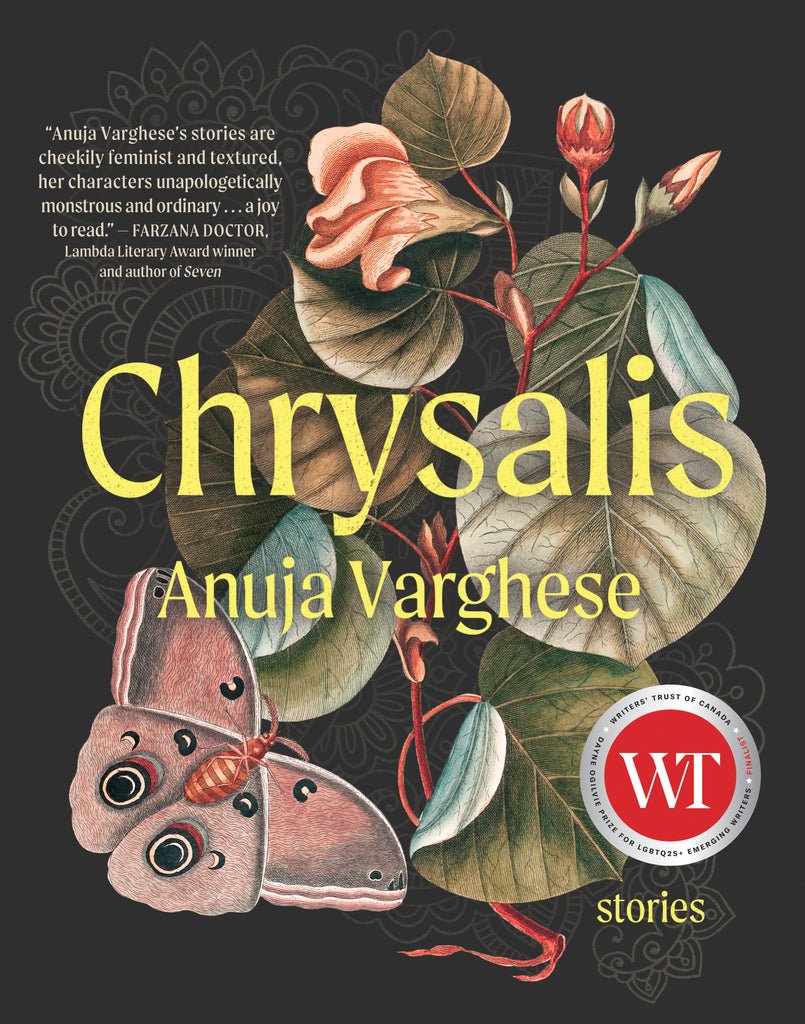

Chrysalis. Anuja Varghese. House of Anansi Press. $22.99 CDN, 208 pp., ISBN 9781487011666

Anuja Varghese is a spellbinding storyteller.

If it’s a cliché now to say that a short story can contain a whole world, then I’ll say that Varghese’s stories capture whole journeys. In a matter of pages, the author takes us across Toronto on a streetcar in search of salvation, across generations and continents to fulfill a promise, or across the ineffable intricacies of human desire to arrive at (self-)love. The best stories in this collection do much emotional heavy lifting through taut, economical prose, capturing meaning in precise and memorable images (a mother and her newborn as a “multi-limbed beast, always hungry, eyes on the Hills;” a mall on fire as a woman “twirling with flowers on her feet drift[s] away;” and someone scooping a cat’s “lithe body” onto their lap, sinking “the knife into his furry neck”). These are stories that don’t shy away from violence, but instead stay in its terrifying grip to explore our human search for tenderness.

Varghese has a gift for lending strange tones to mundane affairs like failed relationships, sibling rivalry, and deceit. Many of the stories in Chrysalis work through the narrative turn, which reignites what came before, surprising us with deeper insight. This approach makes her stories fresh and resonant instead of a rehearsal of well-worn themes. “Milk,” for example, about a bullied brown teenager, does not conclude with a confrontation, revenge, or mutual understanding, but veers towards eroticism, a kind of unlocking of the primal. What we discover about desire is delivered slant, askew—this is a kind of estrangement that tells us the world is more than what we think we know or come to expect. The collection’s most evocative story, “In the Bone Fields,” has the feel of a gothic immigrant saga, a new take on what it means to take root in a place and “belong.” The process of settling and building a legacy in a new land takes on the sinister dimensions that have always been at its core. The immigrant’s inheritance is, indeed, chilling. Another gem, “Remembrance,” drops us into the situation—an opportunity for solidarity—and before we know it, spits us out, leaving us to contemplate what it means to protect someone.

Varghese is at her best when she writes about the erotic absurdity of sex. The possibility of pleasure is always present, but so is the long and unsatisfying road to get there. The description of a man “panting as he pounds away at” a woman, “as one might pound a flank of steak to soften it” in “Dreams of Drowning Girls,” for example, is deeply hilarious, tragic, and ultimately true. It is not easy to write about sex (and what it means for people), and it seems Varghese has found just the right balance of seduction, brutality, and humour.

At the core of this collection are women who have made something of and for themselves, by any means necessary. The narrator of “A Cure for Fear of Screaming,” is trying to find her voice and will stop at nothing, absolutely nothing, to hear herself for the first time. The narrator of “Midnight at the Oasis,” carves out family for herself, even if it means she has to disappoint and betray the conventions others have made for her. And the protagonist of “Chrysalis” realizes she can make a decision. These are stories of the most common people, touched with a sense of weird, of the beyond, of magic.

Vinh Nguyen is an educator and writer. His writing appears in Brick, The Malahat Review, PRISM international, and Grain. He edits nonfiction for The New Quarterly. His memoir The Migrant Rain Falls in Reverse is forthcoming in 2025.