Land Beyond the Country: On Matthew James Weigel's Whitemud Walking by Ben Robinson

Whitemud Walking. Matthew James Weigel. Coach House Books. $23.95 CDN, 144 pp., ISBN 9781552454411

No book I read last year has stuck with me more than Matthew James Weigel’s Whitemud Walking.

The Dënësųłinë́ & Métis writer’s debut collection, published by Coach House Books in April 2022, is a powerful revision of place-based writing that looks beyond “Canadian” literature to a literature of place not constrained by the country. Rather than focusing on arbitrary administrative boundaries which reinforce the idea that Weigel’s hometown of Edmonton is only ~200 years old, by centring his investigations on treaty, Weigel asserts a different foundation. “Here,” he writes, “treaty means reciprocity and obligation. Here, treaty lasts forever.”

Weigel’s approach to treaty is multifaceted, addressing it as ceremony, as text, as political process. In “RELEVANT FACTS AND NUMERALS OF TREATY AND MÉTIS SCRIP,” one of several recurring sequences in the collection, Weigel documents his encounter with physical copies of Treaties 6 & 11 at Library and Archives Canada, engaging the texts with a graphic designer’s attention to layout:

The capital letters are approximately 11 mm tall.

‘NUMBER ELEVEN’ letter ‘E’s are 6 mm wide.

TREATY letter Es are 9 mm wide.

By noting the document’s inexactness, Weigel highlights the limits of the written treaty – a gesture that is made even more explicit in “THE BUFFALO WILL SOON BE EXTERMINATED” where he writes “the text is not the treaty.” In this, Weigel has found an analog for one of the central problems of place-based writing: in the same way that the written place is not the place, the written treaty is not the treaty.

One stay against this slippage between the real and the written in Whitemud Walking is the foregrounding of embodiment. Throughout the book, Weigel balances his historical investigation into treaty-making, Métis scrip, and colonial archives with the presence of his own body (I’ll abandon the pretext of “the speaker,” as the direct insertion of the personal into the historical record seems to be the point). In the collection’s opening piece, “INSIDE THE POP-UP BOX,” the presence of his body poses a challenge to the primacy of text:

Beyond us is the new building,

the building they say will be staffed with robots,

arms of a safe temperature

reminding us

that to touch a document is to take a piece of it with you

and to leave a piece of you behind,

and it is in this exchange we must climate control,

in dereciprocal programming.

And when only the dead and programmed can see my kin,

no one will see my kin.

Here, Weigel highlights all the measures that are in place to keep the physical treaty stable and static. To interact directly with the document would threaten its stability both materially and politically.

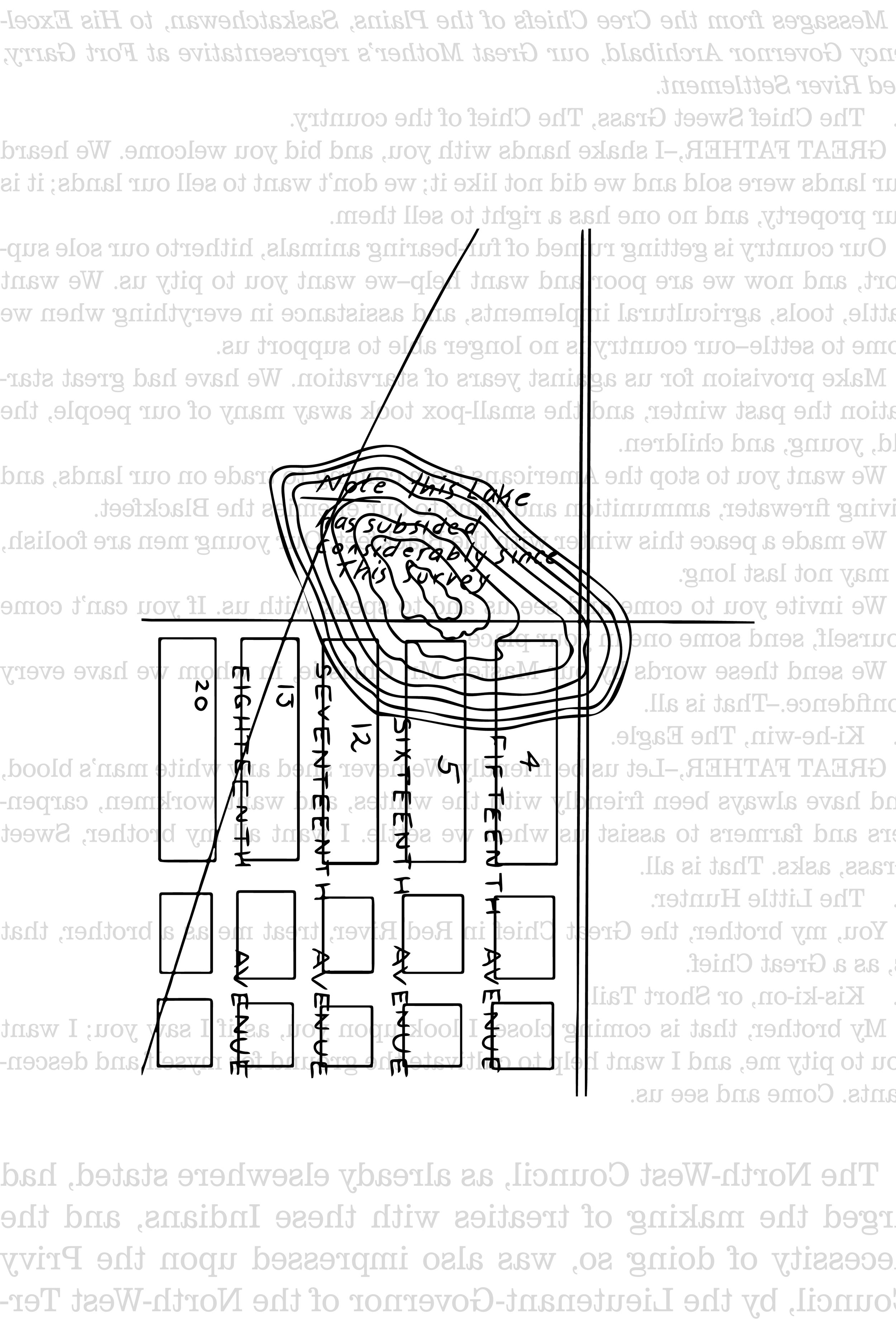

Weigel also brings this tension around the difficulty of textual representation into the form of the book itself. One way to get around the limits of writing is to use forms other than writing. While engagement with visuals in Canadian poetry can feel like an afterthought at times (with the obvious exception of visual poetry), Weigel has the technical and aesthetic skills to make Whitemud Walking feel truly multimedia rather than a poetry collection with supporting images. He reproduces and overlays maps, photographs, calligraphy and signatures to push past the limitations of word-processed text – each of the forms coming together, to create a stronger and stranger whole.

(From Whitemud Walking, p. 105, reproduced with permission from Coach House Books)

The word “poems” is noticeably absent from the book’s cover and questions of genre and categorization are apparent from the outset; the Library of Congress Genre Form Terms on the colophon include poetry, visual poetry and nonfiction, the body of the text names historiography and treaty poetry. Whitemud Walking pushes the form of the book so far that some readers were convinced the second section, which reproduces the crown’s view of treaty negotiations in the margins while leaving the majority of the page blank, was a misprint.

Weigel’s formal experimentation expands the role of the “writer” within the bookmaking process as he integrates layout and typesetting into the creative work of the text. “Coach House Books was very generous during the publishing process,” he writes, “allowing me to have a hand in nearly every part of production…We even deliberated over the book’s trim size, deciding on a slightly non-standard dimension that allowed the area of the page to fit the visual pieces as best as possible.” For a book that shifts forms so readily, Weigel’s skill with InDesign and Photoshop seem especially important. I sense that Whitemud Walking flows as well as it does and maintains a sense of cohesion despite the formal experimentation because Weigel was involved in every step of the process. Tellingly, both Weigel and Coach House’s managing editor Crystal Sikma were named when the book won the Alcuin Society’s first prize for poetry book design.

I wonder about this idea that the true treaty lies beyond the bounds of the text and whether this concept applies to Weigel’s book more generally – that ultimately, what this book is referencing and trying to invoke through the body, through visuals, through form, will always lie more fully outside the pages of the book. In the opening to “THE BUFFALO WILL SOON BE EXTERMINATED,” Weigel writes:

When academics speak about books they some-

times use words like paratext to talk about the

material that surrounds the text.

Perhaps then, Whitemud Walking is a paratext of the land – or vice versa? The book surrounding the land, land surrounding the book, a meeting of text and place:

1876 and my uncle is at pêhonân,

signs the treaty with a leftward slant.

It is August and the aspens bend in the wind.

Ben Robinson is a poet, musician and librarian. The Book of Benjamin is forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in the fall of 2023. He has only ever lived in Hamilton, Ontario on the traditional territories of the Erie, Neutral, Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee and Mississaugas. You can find him online at benrobinson.work.