Gregory Betts Reviews Peter Jaeger’s 10,000 Hand-Drawn Questions

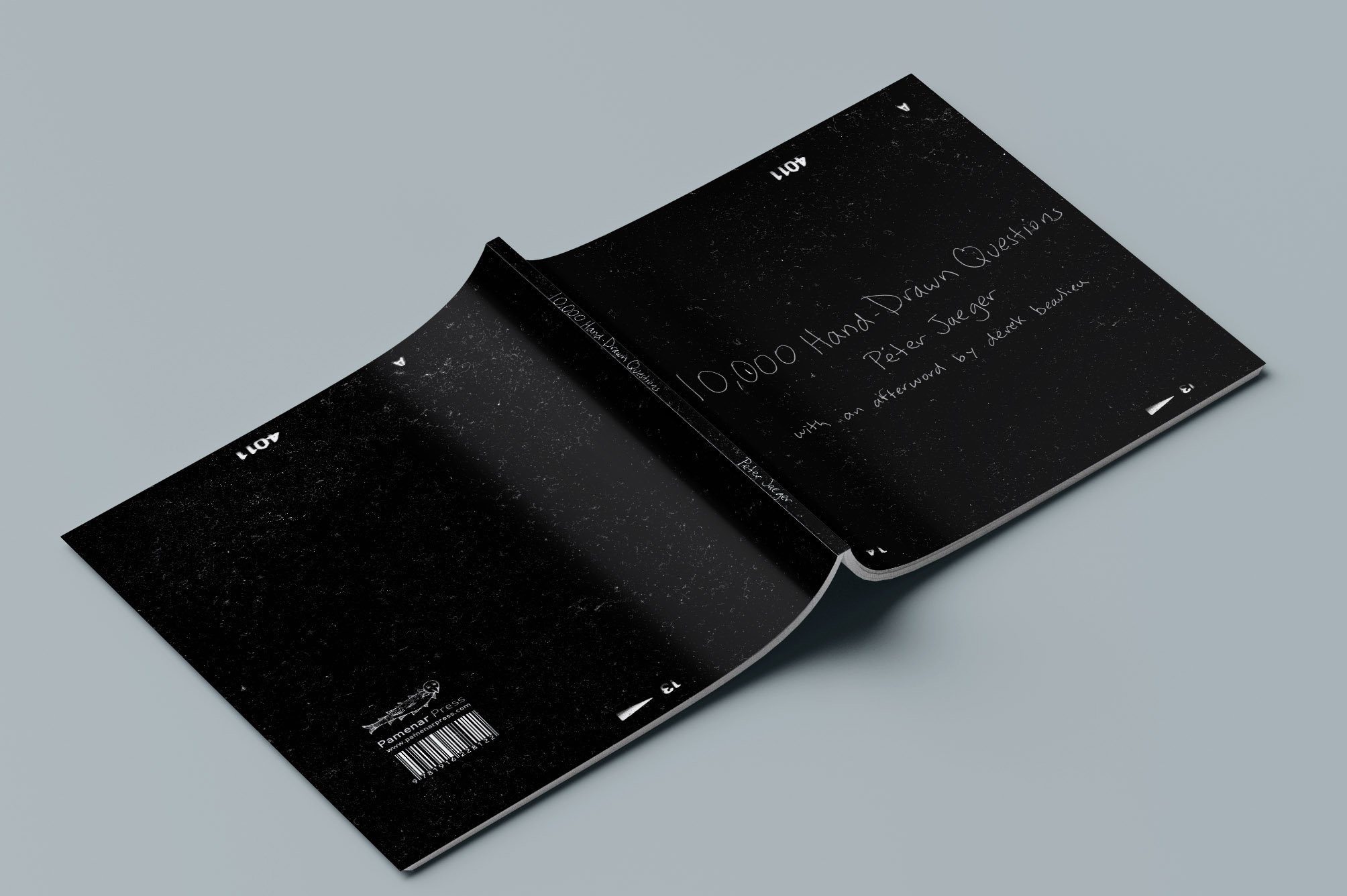

Jaeger, Peter. 10,000 Hand-Drawn Questions. Pamenar Press, £14.00, 144 pp. ISBN 9781916228108.

Answering Jaeger

Peter Jaeger has produced a daring book that claims to contain 10,000 questions, all hand-drawn provocations that embed the content of the poetry in each unanswered question. By way of review, I want to explore this conceit by trying to answer just one of his questions, using that question to see if one such entry in the book, chosen at random, ultimately leads back to and illuminates the ambitions of the book as a whole. I let the book fall open near the middle and picked one example from the centre of that page: “Have we always been here?”

This selection typifies the kinds of questions Jaeger asks throughout the book. He does not use faux naïf, leading, or rhetorical questions. Jaeger’s questions interrupt – or disrupt – narrative possibility. They are the kinds of question one might ask in the middle of a conversation late at night, after a thoughtful pause, and not really expect anyone to answer. You could either follow the philosophical streak all the way into that rosy dawn, or smile politely and change the subject. Jaeger does the latter. Each question leads to another question as Jaeger interrupts each interruption, sending the conversation careening in another direction. Thus, he asks coyly, “What was the question?”

‘Have we always been here?’ Have we always been stuck in a moment in which our philosophical asides, our attempts to open a moment up to thinking, are passed over and missed? Questions is a game played in Hamlet, but it’s played only by the fools Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Tom Stoppard’s examination of their lives in and around their scenes in Hamlet capitalizes upon their inability to think beyond the existentialist dilemma of a meaningless present over which the characters have no control. ‘Have we always been here?’ has a note of lament at the loss in this moment, a plea for a nostalgia just beyond memory, with echoes of Beckett on our ability to change things regardless of how they once were. Thus, he asks coyly, “What has been done with us?”

This moment, though, the moment in which Jaeger’s book appears, adds a bitter poignancy to the lament. Public discourse has gotten so caustic and divided today that we have lost access to any unifying alternative. Jonathan Haidt, in The Atlantic, laments the stupefaction of this era, which he characterizes as the result of a dissolution of trust, authority, and credibility: “We are disoriented, unable to speak the same language or recognize the same truth. We are cut off from one another and from the past.” In the age of social media and the ideological silos sustained by information access that is overwhelmingly governed by belief-affirming algorithms, the terms of truth are fundamentally suspect and inaccessible. “Have we always been” stuck in such silos? In such a moment of truthlessness, convincing answers become impossible. Everything is an unanswered question lost in an endless feed, an endless feud. Thus, Jaeger asks coyly, “Does handwrit[ing] reflect the age? How big is the gap between skin and screen?”

Jaeger’s book is not a book about social media, though, even if its stream of questions seems analogous. These are hand-written works calling attention to the body, not the machine. Isn’t it strange how, half a millennia after the invention of print, everybody just accepts the same font, the same kerning, the same minimalist typography? Twitter is the final triumph of Helvetica’s globalist aspirations. Jaeger’s feed, in a book rather than a tweet, bears the mark of the body’s presence, thereby posing its questions as antidotes to the faux answers provided by social media streams. Each online post is just an empty promise, a glimpse of feigned certitude – food, clothes, jokes, and posed scenes all seem to assert presence, but yet deliver only illusion. Thus, ‘Have we always been here?’ resists the empty illusions of affect in social media. ‘Have we always been here?’ permits the possibility of off-brand messaging, a slip of the mask, an off button for the persona, and an outside, a here, to remember. The messy handwriting that spills off the page in every direction reminds us of the inaccessibility of completeness, of answers in the current moment. It isn’t proposing a return to the real, but presenting a reminder of the hyperreal. Thus, he asks coyly, “How authentic are these representations of questions?”

In the collection’s afterword, Canadian poet Derek Beaulieu asks leading questions that embed their answers in the asking. His aim is to historicize this kind of writing within the context of other attempts to write using only questions. He points out the fact that Jaeger does not describe his script as “hand-written”, but rather as “hand-drawn.” The difference shifts the mode of production from text to visual art, and the work itself moves from an act of discourse to a material representation. Each page of questions becomes an experience unto itself. In art critic John Berger’s account, words describe or explain the world, but seeing establishes our place within it. Consequently, the question ‘Have we always been here?’ does not present a question that disrupts an imagined conversation, does not present an interruptive philosophical musing, but is, instead, a self-reflective acknowledgement that the work of art you are engaging with has a material presence saturating its performance as a moment of discourse. As bpNichol writes in his personification of text in Craft Dinner, “you turn the page and i am here […] my existence begins as you turn the pages & begin to read me.” Jaeger’s text might seem more uncertain, but the answer to the question is now clear: for as the object only exists through the representation of the question being asked, the answer is the perpetual presence of its questioning.Thus, he asks coyly, “Are the only true thoughts those that do not grasp their own meaning?”

I have been meditating on one question in a book that claims to contain 10,000 (in truth, I would estimate there are about 600 questions in the book, though as mentioned above, we are presented only with fragments of the pages, implying the rest).

Had I taken up a different question – for instance, “Are we reflections of something else?”, “How soon is now?”, or, “Is there a feasible exit strategy?”, I would likely have ended up in the same or similar spot. The book is a daring event of simultaneous self-declaration and self-evisceration, a resonant stasis built of suggestive but elusive riddles. Some of the questions, such as, “Would you prefer a cardboard coffin?”, “Do you believe in miracles?”, and “Did you take too much LSD in high school?”, limit interrogation by having more definite answers, or rather, by permitting answers that lead readers into their own experience rather than back towards the project itself. The book’s triumph is a wallow in the magical space outside of author, reader, and fictional universe. Thus, he grounds the poetics of the text in its own hermetic evanescence, even coyly asking, “Should I make it more self-referential?”

Works Cited

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. New York: Penguin, 1972.

Haidt, Jonathan. “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.” The Atlantic. May 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/05/social-media-democracy-trust-babel/629369/

Nichol, bp. Craft Dinner. Toronto: Aya Press, 1978.

Shakespeare, William. The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. 1602. London: The Folio Society, 1954.

Stoppard, Tom. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. New York: Grove Press, 1967.

Gregory Betts is a poet, professor, and editor at Brock University. He has published 22 books, including 10 collections of poetry. His most recent books include Finding Nothing: The VanGarde, 1959-1975 (University of Toronto Press 2021) and The Fabulous Op (with Gary Barwin, Beir Bua Press 2022). He is the curator of the bpNichol.ca Digital Archive.