Flight Forward

It began like a lot of things while writing this story – by chance.

Jen Rawlinson interviews Pasha Malla

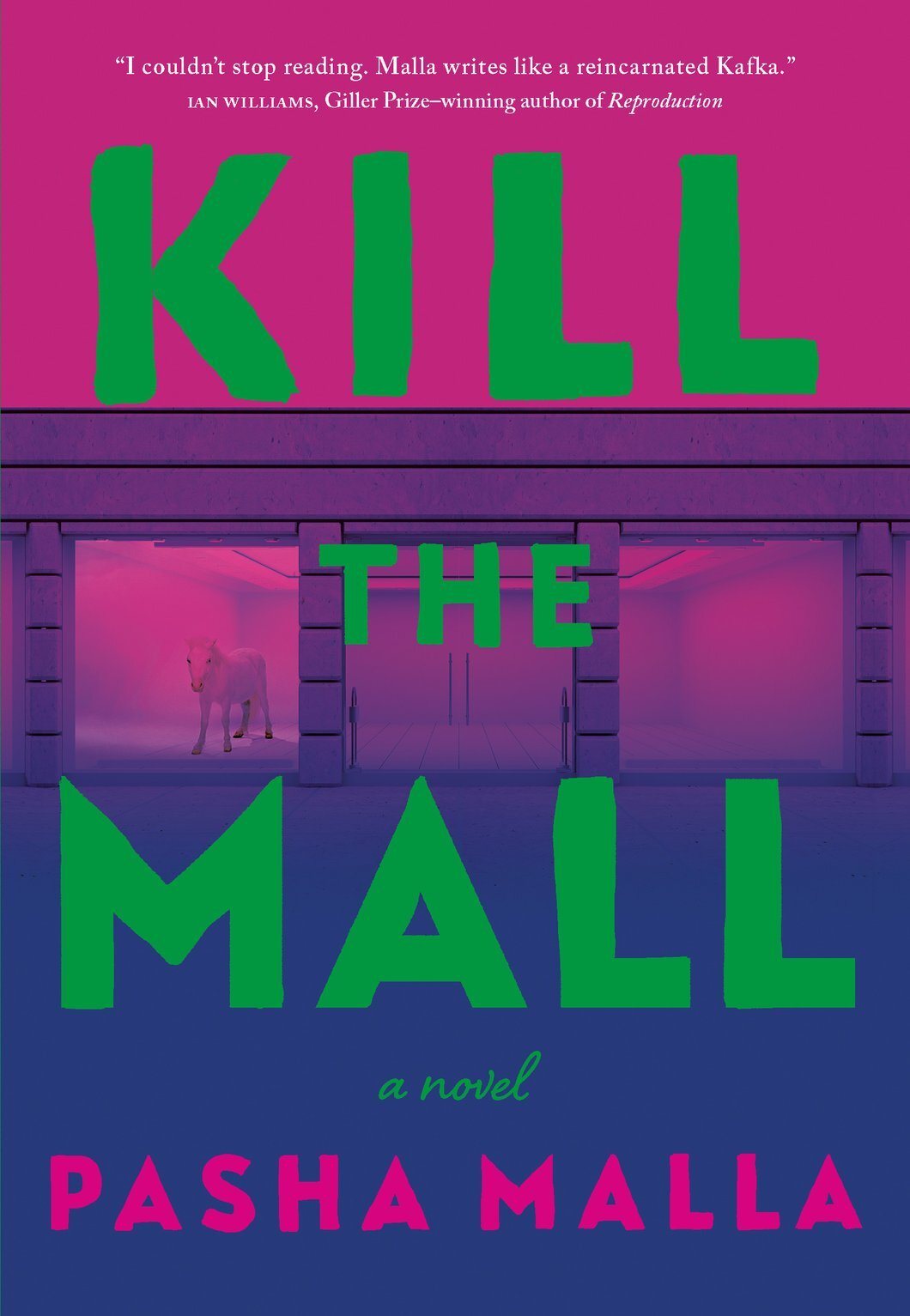

Pasha Malla is the author of five works of poetry and fiction, including the story collection The Withdrawal Method and the novel People Park. His fiction has won the Danuta Gleed Literary Award, the Trillium Book Prize, an Arthur Ellis Award and several National Magazine awards. It has also been shortlisted for the Amazon.ca Best First Novel Award and the Commonwealth Prize, and longlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. Pasha Malla lives in Hamilton.

Pasha Malla. Kill the Mall. Knopf Canada. $25.00, 256 pp., ISBN: 978-0-735273-49-8

Jen Rawlinson: In our last interview with you, you described the project you were working on as one that honours your love of gothic novels and 1970s horror movies. Can you talk about how those things came together to become Kill the Mall?

Pasha Malla: I think at first I just started with a vague idea of a location, aesthetic and atmosphere for the book, and borrowing from Ann Radcliff and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre seemed to fit the bill as a way of destabilizing the setting and making some sort of commentary about the grotesqueries of consumerism. Obviously that changed a lot as I got typing, though I still like to think that the unsettling feeling prevails.

JR: I want to ask about what research went into creating the mall in Kill the Mall. As a fellow Hamiltonian, all I could picture were the escalators of Lime Ridge Mall. I imagined that the House of Blues sits approximately where Sunrise Records is located. Is the mall based on Lime Ridge? Is it a mix of several different real-life malls? Or is it drawn entirely from imagination?

PM: Research! Ha! No, no research, really, short of spending a lot of time in a lot of malls over the course of my life. (I really like malls.) The only mall I had in mind here was the London Mews (or "Smuggler's Alley"), which hasn't existed for a long time. I worked there when I was in high school, at the Famous Players movie theatre, which at the time was one of like four open businesses in the whole mall, so every time I went to work I had to walk this gauntlet of abandoned, empty stores. It was super creepy and the experience has always stayed with me. That said, I hope the mall in the book is generic enough that the story is transferrable onto any real-world mall – Lime Ridge works, for sure.

JR: In Fugue States you engage with – and rebel against – realist conventions. How does Kill the Mall’s absurdism fit into that conversation? Is it part of the rebellion or was absurdism something you wanted to explore for its own sake?

PM: I don't know if I'm rebelling against anything here, beyond my own propensity to plan and structure and conceptualize my books. The goal with this one was to start with a vague dramatic situation and just type – poaching César Aira's "flight forward" technique – and I set up a schedule where the book was going to be twelve parts, and I would type one part per month, without revision, so that the book would be done in a year. My first novel took me eight years to write, and Fugue States took six, so I hoped that this one would be written quickly as a kind of reaction against my own previous, laborious process.

JR: Horror-comedy is a subgenre that I feel doesn’t get as much love as it deserves, and Kill the Mall is both laugh-out-loud funny and eyebrows-to-the-sky disturbing. Can you talk about what drew you to this particular blend of genres?

PM: I don't know if I was actively thinking about genre; I just typed stuff that I found fun or curious or entertaining, and I probably gravitate naturally to things that are a little bizarre but ironized with humour in some way. Have you seen In Fabric? I saw that well after Kill the Mall was finished, but it's an eerily appropriate companion film for this book, I think, with a similar blend of absurdity and stylized horror and dry comedy – and it takes place in a shopping centre, too.

JR: The hero of Kill the Mall is quite a unique character. His mix of imagination, anxiety, ineffectualness and naivete make him seem very real and grounded, but also exaggerated and cartoonish. What went into crafting this character, how did you develop this narrative voice, and how did you balance his realism with his absurdity?

PM: Yeah, he's a total caricature. The voice is a lot more obvious in the audiobook, which Anand Rajaram voiced masterfully. My idea was that this character is an Oxford-educated South Asian man of a certain age who speaks (and thinks) with a kind of contrived, antiquated formality – the closest popular amalgam I can think of is Salman Rushdie, though my guy is much more mannered and oblivious. I thought that would create good tension with all the weird stuff going on around him, similar to the narrators of some gothic novels, or what you find in a lot of H.G. Wells' books.

JR: The titular mall in Kill the Mall is both more and less than it appears to be. When our hero starts his residency, he is surprised by how few people actually patronize it, and as the story progresses, he discovers just how many secrets a mall can keep. Why did you choose to set the novel in a mall, and what is it that makes malls so rife for horror?

PM: I think malls are really fertile places for any sort of story, I've just had this memory floating around for twenty-five years of working in a really spooky one. But the dead or dying mall is such a poignant symbol of the last gasps of a certain kind of free enterprise, and I suppose that interested me, too. But, again, my main goal with this book wasn't to push an agenda or message as I might have done in my past two novels. This was mainly about having fun, making myself laugh, and keeping the writing process active and vibrant and entertaining to myself. I succeeded at that, for sure – I had such a great time writing this book! – though I have no idea how or if that will translate to a reader's experience of the published novel.

JR: In an interview with Maisonneuve, you said that books are nice because they have no value. Books are one of the increasingly few things that resist the production/consumption cycle under capitalism. I see this tension reflected in the relationship between our hero, who makes work for the sake of making work, and Mr. Ponytail, whose art is something that can be easily consumed by the masses. Did this tension come from the setting or was the setting necessary to talk about this tension?

PM: Did I say that? I mean, a book is a commodity. I wanted this book to explore the tension – or hypocrisy – of critiquing capitalism while being published (and paid, though not very much) by a mega-corporation, and how so much of our communication and social interaction is mediated by corporations – I'm sending you this message via Google, e.g. – as well as that we're all essentially disempowered, passive residents in the massive, failing mall of late capitalist society. But I didn't want the book to be preachy or take that stuff on too literally, but more tonally: I hope the ways in which sinister, hegemonic power manifests in the book are sort of baroque and grotesque in an expressionist, absurdist way.

JR: When the hero of Kill the Mall tries to leave to check up on his bicycle, the mall’s hallways twist and expand in confusing ways so that he always ends up where he began. His feelings of isolation and confinement hit a lot closer to home in our current reality under lockdown. Was it an intentional choice to include feelings of isolation and confinement or did that develop over the writing of the book?

PM: Don't we all feel trapped and isolated, sometimes – even when we're not sequestered to our homes during a global pandemic?

JR: From those weird hairy dust bunnies you might see gathering in corners of oft used public spaces to sleek and praiseworthy up-dos, hair plays an important role in Kill the Mall in ways both alluring and repulsive. Did you place this emphasis on hair because it can create strong feelings of attraction or disgust or were there other reasons behind this choice?

PM: It began like a lot of things while writing this story – by chance. I was typing an early scene and got a dog hair in my mouth (this happens far too often in our house), and I pulled it off my tongue with disgust and then just folded it into the scene I was writing. But then as I kept going hair seemed to manifest some of the larger thematic stuff I was thinking about (aesthetics, waste, consumption, repulsion, etc.), so it seemed to make sense to develop it a bit more as a motif. Not that it, or anything, is meant to make too much sense in this book!

JR: What are you working on now?

PM: A novel that I've had in the works in some fashion since 2002. It's based on the true story of an Italian physicist who went missing in 1938, though I'm taking some liberties with the history, and I'm also including a bunch of writing about movies – including the dubbed Italian version of The Fly, La Mosca, which is really, really great for a bunch of reasons, only one of which is that whoever voiced Jeff Goldblum's part sounds like a sexy opera singer after three classes of champagne.

Jen Rawlinson is a book person: Reader. Writer. Designer. Reviewer. Editor. ebook Maker. When things go bump in the night, she investigates. Her writing has appeared in the We Are Horror. You can follow her on Twitter, where she tweets sporadically.