Uncanny, Ferocious, Funny

The cornerstone of these stories is laughter. Laughter in its variations and its scales. Laughter when you are angry; laughter when what you feel is so unbearable; laughter when you want to feel strong; laughter because of joy. Laughter always as power.

Trevor Corkum interviews the Souvankham Thammavongsa

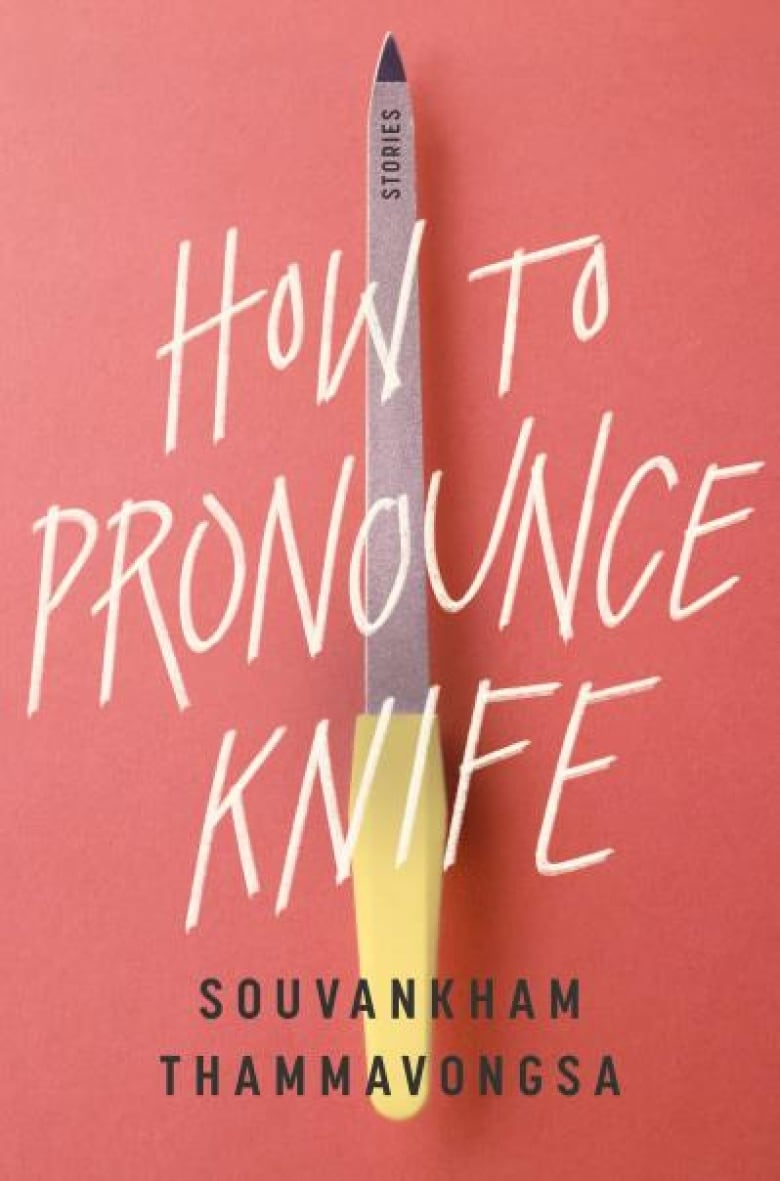

Souvankham Thammavongsa's first story collection, How to Pronounce Knife, will be published by Little, Brown (U.S.), McClelland & Stewart/Penguin Random House (Canada), and Bloomsbury (U.K.) in April 2020. Her stories have won an O. Henry Award and appeared in Harper's Magazine, The Paris Review, The Atlantic, Granta, NOON, The Believer, Best American Nonrequired Reading 2018, and O. Henry Prize Stories 2019. She is the author of four books of poetry, Cluster (2019); Light (2013), winner of the Trillium Book Award for Poetry; Found (2007), now a short film; and Small Argument (2003), winner of the ReLit prize. She has been called "one of the most striking voices to emerge in Canadian poetry in a generation" (The Walrus). She is working on her first novel. (Photo credit: Jennifer Rowsom)

Souvankham Thammavongsa. How to Pronounce Knife. McClelland & Stewart. $24.95, 192 pp., ISBN: 9780771094606.

Congrats on the release of your debut collection of fiction, Souvankham. It’s an exceptional read. For those not familiar with your work, how would you describe the stories?

The stories are uncanny, ferocious, funny. The cornerstone of these stories is laughter. Laughter in its variations and its scales. Laughter when you are angry; laughter when what you feel is so unbearable; laughter when you want to feel strong; laughter because of joy. Laughter always as power.

But I feel shy about describing them myself. How about we let Mary Gaitskill do it? She said, “Powerhouses of feeling and depth.”

While this is your first work of fiction, you’re an award-winning poet with several published collections. How did you find the transition to working in this new genre?

I didn’t think of writing fiction as working in a new genre. I just thought of it as writing. It is like an athlete who has been playing basketball and now wants to play baseball. I know what a three-point shot is, but I also know it means nothing if I come to baseball and did that. An athlete is a professional. They know they have to hit a home run to be meaningful. That’s what they are there to do and they will get the job done.

Your stories follow the lives of immigrants and refugees to Canada, the people who often do the “grunt work of the world”, to quote one of the stories. These are folks whose stories are rarely told, who often remain invisible background extras in other literary creations. Why was it important to focus your work on these characters?

I think stories of immigrants and refugees are told. We see and hear them on the news and in literature. But whenever I encountered stories of immigrants and refugees they are only ever sad and terribly tragic — rightly so — but that is a very narrow view of who we really are. We are hilarious and furious and ungrateful and ferocious, too. Stories of refugees are also only ever about being in the camps. None of my stories take place in the camps and no one has flies crawling into their nose. These are people who live next door, who are just trying to get to the next hour, the next day, the next year. They just want a chance to live and to matter and to love too.

In one of the stories, “Picking Worms,” a young woman joins her mother picking worms for cash. Her mother is an expert picker, but later in the story the girl’s prom date, a white teenaged boy, becomes manager of the operation, even though he’s less qualified and less successful than the narrator’s mother. In a nutshell, you seem to have captured the insidious nature of structural racism at work in Canadian society. What was the inspiration for this story?

For me, it is not a story about that white teenaged boy. It’s the power of the girl to say “no.” The teenaged boy becomes manager and he’s boss, but he’s still a boy. Who has more power than a boy? A girl who can break his heart.

I was watching a movie and a scene in it that made me so angry. A soldier is just sitting there and an Asian woman comes by and says “Ten dollars? Ten dollars?” because she is a prostitute, and then adds “Me love you long time.” I hated that moment. So I wrote “Picking Worms” and made that woman the hero, the centre of the story, and not some bit. That’s what’s lovely about writing — I have that power to change the story.

In another story, “You Are So Embarrassing”, a mother estranged from her adult daughter revisits their past relationship. In this story — like so many in the collection — you focus on the conflicts that arise between parents and children when various boundaries are breached. Can you talk about this particular vein of conflict further?

We know a lot about racism that happens at school, at the workplace, from strangers, or just institutionally and structurally and historically — but there’s a different kind of racism we don’t get to see too often. It’s how racism can be private. The kind where what a child learns at school is brought home and destroys the family, or a wife calls her husband a different name to assimilate him without considering his own desire, or how a man just wanting a chance at love can’t ever be seen as potential because his job at the factory is to slit the necks of chickens. It’s what we do to each other and ourselves in private. The outside world is already doing this. What happens when the racism enters a private sphere and comes from your own blood, your own self?

Many of your stories feature younger protagonists, girls and young women who quietly observe the successes and failures, the humiliations and triumphs of their parents. I’m reminded of the work of Alice Munro and Madeline Thien, whose stories also feature young female observers. Do you have literary heroes? Who has influenced your short fiction work, in particular?

True, but there are also women who says things like “It’s because you are a fucking man, isn’t it?” when her brother gets more cash tips than her; little girls who say things like “I’m twelve, you creepy fuck! I’ll cut it off! We’ll see what’s sexy then!” when a man calls them sexy; shop-owners who say “Fuck you! Fuck you all into hell!” when a customer is condescendingly racist; and a seventy-year-old woman who says, “He was a man, and I was bored.”

I love Alice Munro and Madeleine Thien. I’ve been reading Alice Munro for a long time. I love how lethal she is, but you don’t even see it coming because she is so plain in her delivery. I also really love Tennessee Williams and Carson McCullers and Flannery O’Connor. They love the people they write about and they are very clear-eyed and unflinching.

My family has influenced my short fiction. There is so much there thanks to them and they are so entertaining and I haven’t come across people like them in real life or in literature. I wanted to capture their sense of humour, their ferocity, and not just their sadness.

Music also crops up in the stories, in particular country music (Randy Travis plays a big role, and Dolly Parton has a cameo). There’s a sense that these musical icons signify and represent a type of cultural currency that the characters themselves — like the narrator’s mother in “Randy Travis” — find it impossible to acquire. In “Randy Travis,”, the narrator’s mother is so obsessed with Randy Travis that it slowly destroys her marriage, and her husband, in an act of generosity, buys her tickets to a concert in the USA at great personal sacrifice. What do these cultural figures represent for your characters? And why country music, in particular?

I really love country music. I could relate to Dolly Parton’s song about a coat her mother sewed with a bunch of rags and she was so proud of it, but then when she wore it to school she realized it was rags. I love the simplicity and how bare and plain the language is in country music. The story is the most important thing in country music and I am interested in story — told plainly and simply.

Many of the stories in the collection have been previously published in some of the top literary journals and magazines in the world— The Paris Review, Granta, and The Atlantic. Did you feel any kind of pressure or expectation, putting the collection together?

No. I am forty-two years old. I expect this.

I have been writing for more than twenty-five years. When I was younger, I printed chapbooks and sold them out of my school knapsack at small press fairs. I worked in the research department for a financial newsletter for fifteen years. I counted fat bags of cash five levels below the ground for a bank in downtown Toronto. I learned to prepare taxes for a living.

I was writing when there was no email or internet. I was writing when there was no social media. I was writing when we used typewriters and had to measure the margins. I was writing when typing forty words-per-minute was impressive and typing seventy words-per-minute is just competence. I wrote four poetry books over a span of twenty years.

I have wanted this for a long time. I have always been writing, but now I have an agent, Sarah Bowlin, and she sends my stories to these magazines. Isn’t that what an agent does — get your stories into places like this? I don’t have to mail submissions in with a self-addressed, stamped envelope and wait two years anymore. It is so fast!

Finally, I understand you’re working on a novel now. Can you tell us any more about the project?

I can’t, for secret reasons. But I can say there’s boxing and to get the boxing right, I took lessons at the United Boxing Club in Toronto on Bloor Street. At first it was for research. I wanted to know what it was like to throw a punch, to absorb one, to control the fight and the centreline. It has been such a brilliant joy to be boxing that I did not stop. I go three or four times a week and feel like no one can mess with me.

Trevor Corkum’s fiction, non-fiction, and journalism have appeared widely across Canada and internationally. His debut novel The Electric Boy is forthcoming with Doubleday Canada.