Excavating the Complexities of Humans

There is no better place to excavate the complexities of humans than through fiction.

Jenny Ferguson interviews Ava Homa

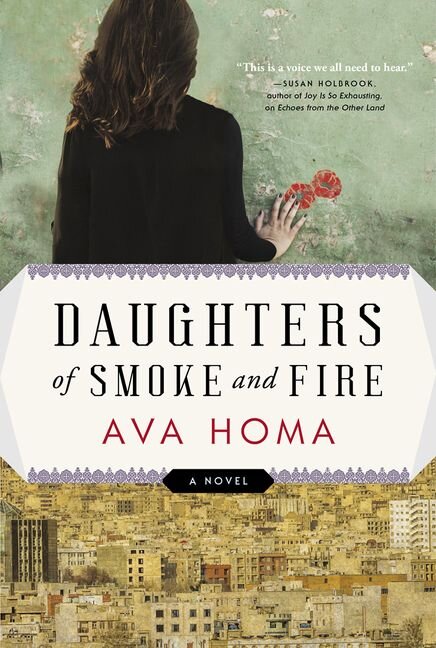

Ava Homa’s collection of short stories, Echoes from the Other Land, was nominated for the Frank O’Connor International Prize, and she is the inaugural recipient of the PEN Canada-Humber College Writers-In-Exile Scholarship. Daughters of Smoke and Fire is her debut novel.

Ava Homa. Daughters of Smoke and Fire. Harper Collins Canada. $22.99, 320pp., ISBN: 9781443460132

Ava Homa is an activist, journalist, and fiction writer whose first collection, Echoes from the Other Land, opened up the daily lives of Iranians in minimalist short stories. Now, in her debut novel, Daughters of Smoke and Fire, forthcoming in Canada from HarperCollins and in the US from The Overlook Press, an imprint of ABRAMS, Homa returns to Iran to document the experiences of upwards of 40 million stateless Kurds in fiction.

Leila, the novel’s protagonist, is a budding filmmaker who wants to bring her people’s stories to the world stage. Her younger brother, Chia, is more invested in riskier activism. One night, he disappears from the streets of Tehran. Now Leila must figure out what’s happened to her brother, in an increasingly dangerous political landscape.

Jenny Ferguson: Welcome Ava! You and I were students together at the University of Windsor, many years ago, and I’m thrilled to get to talk to you about Daughters of Smoke and Fire.

My first question is a bit tongue-in-cheek. Since we’re old colleagues, I hope you’ll forgive me. You wrote in the Toronto Star, in January of this year, about terror and the January 2020 Ukraine plane crash, and what it means to be from Iran — living at home or as a member of the diaspora:

My own childhood memories are tinged with the screeches of the air-raid sirens, the stampedes while running to underground shelters. I remember my mother in a frenzy wanting to take my feverish brother, an infant then, to the hospital despite the bombs raining on our border town.

You’ve lived this experience.

So, why fiction? Why tell the story of the Kurdish people in this way rather than, say ,through nonfiction? What do we gain by following Leila’s fictional journey rather than some “verifiably true” story?

Ava Homa: I am excited to speak with you, Jenny, as I have been following your writing journey after graduation with a lot of interest.

I choose fiction because I am more interested in truth than in facts, which to me are merely a means to an end. There is no better place to excavate the complexities of humans — our similarities and differences across borders, race, religion and other superficial walls — than through fiction. My best tool of understanding other cultures has been through reading their literature and so I am offering my best way of introducing my heritage.

Yes, I experienced war firsthand. I have been able to bring a portion of my own lived experiences into the novel, but had I only relied on that, the book wouldn’t be layered and nuanced. To write Daughters of Smoke and Fire, I extensively researched and interviewed political prisoners, torture victims and their families, female freedom fighters Kurds know as Peshmerga, those who face death, who pick up weapons and fight the Islamic State and other oppressive entities. Also, while writing my novel I taught myself a lot of what I was denied while growing up under ethnocide — an assimilate or annihilate policy — I (re)learned Kurdish history, language, even its food. The book is full of yummy recipes to balance the horror of geopolitics with the beauties of everyday life.

JF: That’s in line with my own ethics of fiction. I wonder if you’d be willing to tell us more about the research process — and the most surprising thing you discovered. What’s research like at this level for a fiction writer, and for a writer who can’t go back to Iran? Adib Khorram, who is an excellent YA writer (Darius the Great is Not Okay; and the forthcoming, Darius the Great Deserves Better), whose family is Bahá’í, has never been able to visit Iran but set his novel there. I’m thinking about what it’s like trying to write about your history, in a place that’s no longer accessible to you. Does that complicate research?

AH: Good point. Yes, writing about a place you’re exiled from has its unique challenges, but it also gives you perspective. I left Iran when I was twenty-four, so I was there long enough to experience life and loss as a woman and as a minority in my bones. And I have lived long enough abroad to see Kurds not only as an ostracized ethnic group but as a part of a larger and much more complex geopolitical network. Maneuvering these three languages and worlds — Kurdish, Persian and English — has helped me grow personally and as a writer. When I say commuting between these worlds, I am not referring to only speaking these languages but actually being able to bridge these worlds. I read books and spoke with people in all three languages and spiced things up by imagination to finally complete Daughters of Smoke and Fire.

Perhaps, the most surprising thing I learned was that writing and publishing a novel can take a decade. I also learned how to write a novel mostly by writing it and possibly disposing of a couple of manuscripts along the way. Having a degree in Creative Writing, reading novels, and studying craft are helpful but not enough.

I experimented with placing my fictional characters within important junctures in history. I wrote and rewrote until I was able to subtly and meticulously balance history, politics, and fiction. Weaving fifty years of modern Kurdish history in a novel was an ambitious project. I am lucky I met my wonderful agent Chris Kepner who then connected me with master editors Chelsea Cutchens at The Overlook Press and Jennifer Lambert at Harper Collins. They all helped me make the final changes. I am so grateful to these people for having faith in me when I didn’t have much myself.

JF: I love this. It takes a community! And yes, life and research shape us to be storytellers. Your novel begins in childhood, with Leila, on the day of her younger brother’s birth. Daughters of Smoke and Fire has been compared to Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner, which also begins in childhood — and then sweeps into adulthood and across the world. Why start a book about human rights violations here with a child’s view of the world?

AH: Starting from childhood helped me to explore inherited trauma, growing up in a country as diverse, complex, and misunderstood as Iran, growing up as a survivor of genocide and ethnocide. For example, finding out early in life that everything about one’s identity is criminalized, and yet reclaiming it later. I also got to explore the role that gender plays. Leila and Chia are raised in the same household and with the same parents but their gender significantly changes their experiences.

It also gave me a better chance to weave in those five decades of modern Kurdish history I mentioned above. I wanted to offer my readers a perspective and as much of the big picture as possible. I needed a rather large span of time to show how geopolitics shapes intergenerational family dynamics.

Finally, writing about coming-of-age helps me engage both young adult and adult readers, especially those who have a strong sense of justice and are curious about “the rest of the world” and underrepresented, disenfranchised groups.

JF: That makes a lot of sense, especially when as a novelist you’re engaging with scope. It’s probably the same reason why so many stories about human rights work from a larger scope. You write about human rights — in your fiction, and also as a journalist. Why is it important for authors to continue to write these kinds of stories? Why is it important for readers to read them?

AH: My goal has been to write about humans, and including rights and their violation has been inevitable so far. Outside of writing fiction, I am an activist focused on suicide prevention among Kurdish women. Unfortunately, more and more Kurdish women in Iran, crumbled under a brutal combination of gender, ethnic, economic and political oppression, give up on life. I spoke at the United Nations about it. The situation of the Kurdish women on one side of the border is in stark contrast with that of the empowered Kurdish women in Syria who fought ISIS and were praised in international media. To help these women, I have formed an informal group; we adopt and translate suicide prevention educational material from Canadian sources, train activists in Iran and hold workshops there.

JF: If your reader is moved by Leila’s story — by her family’s story — by the stories of the Kurdish people, what next? What should they do

AH: If more people know about the Kurds, see their humanity, appreciate how they defeated ISIS, fewer of the October 2019 betrayals will happen.

When more people raise their voice, more people write to their representatives, fewer massacres and executions of political prisoners will happen. Kurdish lives won’t be, in Judith Butler’s words, “ungrievable” anymore. Our humanity will be understood by the rest of humans. We won’t be “unpeople” anymore.

JF: Maarsi, Ava. I feel this deeply. Fiction is a place where BIPOC storytellers write and re-write their own humanity. It’s in fiction where I’ve seen my own self best (Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves is still this book for me), where I write myself in all my complications, where others see someone else as fully, completely human for, maybe, the first time.

I look forward to telling everyone I know to read Daughters of Smoke and Fire.

Jenny Ferguson (she/her/hers) is Métis, an activist, a feminist, an auntie, and an accomplice with a PhD. She believes writing and teaching are political acts. Border Markers, her collection of linked flash fiction narratives, is available from NeWest Press. She teaches at Loyola Marymount University and in the Opt-Res MFA Program at the University of British Columbia.