More Solid Footing: An Interview with Fareh Malik

“If you are a poet or writer trying to explore writing about your trauma, remember that you are valued, your story is worth being told, and no one can tell it better than you.” – Fareh Malik

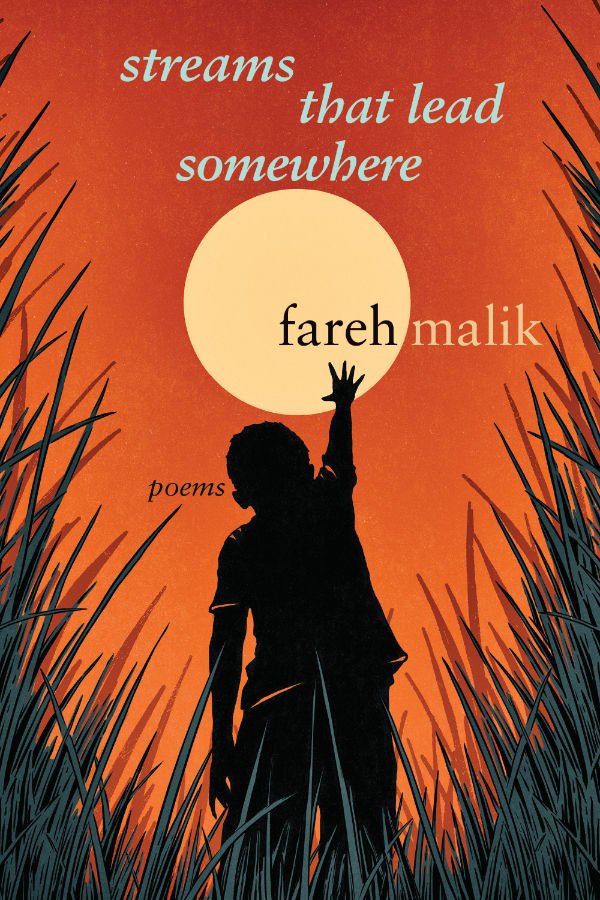

Jaclyn Desforges interviews Fareh Malik about his debut collection, Streams That Lead Somewhere (Mawenzi House, 2022).

Fareh Malik, from Hamilton, Ontario, is also a spoken-word artist. He is the winner of the 2022 RBC/PEN Canada New Voices Award, Hamilton Art’s Shirley Elford Prize, and Muslim Hands Canada’s 2020 Poetry Contest. He was a Best of the Net finalist in 2021, and that same year a Garden Project recipient. His individual works have been published by literary magazines such as Waccamaw Journal, 86 Logic, Lucky Jefferson, Chitro, and Twyckenham Notes. In 2020 some of his work was on exhibit in the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas. Fareh tells the stories of his struggle and of the community around him in the hope that others can find inspiration and companionship in it.

Fareh Malik. Streams That Lead Somewhere. Mawenzi House Publishers, $20.95, 80 pp., ISBN: 9781774150764.

Your collection is split into three sections: streams, rivers, and estuaries. What do these bodies of water mean to you, poetically and symbolically? How do they relate to the themes of your work?

The idea behind having those three sections be symbols for this ever-flowing stream through the book was a deeply personal one. Something that a lot of people may not know about me is that I’ve struggled a great deal with depression and stabilizing my mental health. The book actually flows from this dark and desolate place into more solid footing as you proceed through it. This metaphorical stream that only finds its strength and power through perseverance is something that I wanted to embody in myself as I wrote the book. Water has always been one of my favourite things to write about (even if it is cliché). I think the nature of water and how it can be weak at times, and strong in others – how it can take whatever form it wants – are such cool ways to play with its imagery. It made it a little easier to incorporate it poetically into the book. I love that one of the dominant themes of Streams That Lead Somewhere is mental health and growth, and I think the flowing water imagery is something that is really present in a lot of the book’s poetry as a representation of that.

Streams That Lead Somewhere tackles tough, emotional subjects such as mental illness and racialization. How do you stay grounded while writing trauma? What advice do you have for other poets who want to approach these themes?

The best advice I ever received in the context of writing about personal traumas and hardships came from a poet and friend I really looked up to. She told me that the journey isn’t easy, and you will certainly meet resistance, but the best way to go about it is to just be genuine and true to yourself / your experiences. I’ve stayed grounded while writing about these things because, as I look back, I’m often reminded of the progress I have made and continue to make – that becomes my fuel.

If you are a poet or writer trying to explore writing about your trauma, remember that you are valued, your story is worth being told, and no one can tell it better than you.

It’s hard to pick just one, but I think my favourite poem in this collection is “Clouds.” I love these lines: Every girl I have ever held hands with has said that my hands / felt like clouds. There’s something so surreal about it. Do you have a favourite poem in this book?

I think my favourite poem in the book as I look at it as ink on a page is “Coloured Boys in the Suburbs Are a Novelty.” I don’t know what it is exactly about it that makes me feel so emotionally charged – perhaps it’s just a summation of growing up and finally getting to be introspective about things you didn’t know were messed up or wrong. As a kid, you don’t fully understand how much the community around you can hate or judge you; I’ve had to have my fair share of those conversations with my family.

My poem “After 9/11 the War Spilled Into Our Hometowns & Made Us Grow Up Too Fast & My Homie’s Sister Don’t Wear Her Hijab No More,” which was a Best of the Net finalist this year, was maybe my favourite poem to actually write. It felt intensely cathartic and natural how it came out. If you’ve noticed, the entire poem is a single run on sentence. That is just how my adrenaline-flooded mind thinks in those situations of racism and Islamophobia, and it felt so great to be able to accurately represent myself on the page with regards to those experiences.

How do you hope readers will feel when they finish your collection? What do you want them to come away with?

Since the book’s conception, I have wanted readers to leave this book with a sense of companionship. At first, I didn’t really know why that was my initial thought, but it made more sense as I thought about it. When the book explores these darker times with more desperate circumstances, I’m obviously reminded of the “rock bottoms” in my life. As I look back on them, I think about how what I really wanted was someone to be there with me, telling me it could be okay. I remember wanting friendship, or love, or whatever external force to make it easier. Ultimately, they did; I’m forever grateful for that. I want this book to provide that for someone, no matter how small or fleeting a feeling it may be. I want readers to know that, no matter what they are going through, there are probably people who can relate and support you – perseverance is the key.

When and why did you start writing poetry? And what keeps you writing?

I started writing spoken word poetry in 2012, but never thought of it as a career path. I think it was largely sparked by my love for hip-hop and hip-hop culture, specifically conscious rap. Rappers like Lupe Fiasco, Common, Mos Def, etc. (I could keep going all day) made me want to use this medium to talk about important things in the world. I think I did a free Palestine and anti-war spoken word in my high school talent show, haha. What made me write Streams That Lead Somewhere and what makes me continue writing is a combination of wanting to evoke some positive change in the world, and doing so by following my passion. I am a firm believer that your chances of being your best at something comes from following your passion, and nothing other than writing has made me so eager to work.

How do you move from blank page to poem? What’s your process like, and how has it changed over the years?

My process is an arduous one for sure. Throughout several weeks I will compile a bunch of random metaphors in notebooks, my phone, my arm, whatever. When I can start to see a cohesive thread flow between several of these ideas, I’ll begin connecting them together and creating a first draft. Then I’ll edit the ever-loving life out of it until it’s better (at least, in my opinion).

My process when I first started writing was that I just blurted out any idea I had in the moment out onto the page. It worked, but it required lots of pruning and self-doubt. I like my new way of having fun and interesting metaphors first before creating a poem, essay, or even article.

You’re a dancer as well as a poet. How is dancing similar to poetry as a mode of expression? How is it different? I’m struck by STLS’s emphasis on movement/motion in individual poems, as well as in the central metaphor of water moving towards the ocean.

Through dance, I have always aimed to create cohesive flow and storytelling. That’s something I have definitely brought over into my writing when I am crafting art, whether it be a poem, or theatre work, or anything. The stream in STLS definitely was reminiscent of that, and I really wanted that movement aspect to be at the centre of the storytelling, as I would in dance. I’ve also been getting into intersecting poetry and dance. Applying that work onto new projects has been so cool!

How do you know when a poem is finished?

Honestly, I don’t know that I ever think a poem is finished. I think I could revisit a poem from any point in my life – published or unpublished – and want to make some changes. I understand that as just being in a constant evolution and metamorphosis in your art; there are decisions I would make now that I wouldn’t have made two years ago. There will be decisions I will make years from now that I won’t even think about today. I don’t think it’s a bad thing to not see your work as finished and done with. I see it as a sign that I am still growing and getting better.

What are you reading these days? What are you writing?

As a poet and poetic storyteller, I try to read poetry and creative non-fiction quite frequently. There’s a lot of turnover, but currently I’m reading I Love You, Call Me Back by Sabrina Benaim, Voodoo Hypothesis by Canisia Lubrin, and Ossuaries by Dionne Brand. I’m trying to branch out my work into several other forms of writing. I’ve begun writing a spoken word and play hybrid script for a project. I’ve also started writing essays for my second manuscript, as well as news articles. I think skills in poetry can be so applicable to other forms, and I’m excited to explore!

What else should we know about you?

Please, if you see me out and about or at a reading, come say hi. I’m intensely introverted and won’t say hi first to people, and it apparently makes me seem angry. I often hear that people feel intimidated because I’m quiet and my face at rest is that of a mean old man, but I swear I’m a nice person. I love puppies. I love bubble tea. Be my friend.

Also, please buy my book!

Jaclyn Desforges is the author of a picture book, Why Are You So Quiet? (Annick Press, 2020), and a Danger Flower (Palimpsest Press, 2022). Jaclyn is a Pushcart-nominated writer and the winner of the 2018 RBC/PEN Canada New Voices award, the 2019 Hamilton Public Library Freda Waldon Award for Fiction, the 2019 Judy Marsales Real Estate Ltd. Award for Poetry, and a 2020 Hamilton Emerging Artist Award for Writing. Her first chapbook, Hello Nice Man, was published by Anstruther Press in 2019. Jaclyn’s writing has been featured in Room Magazine, THIS Magazine, The Puritan, The Fiddlehead, Contemporary Verse 2, Minola Review and others. Jaclyn is currently writing a collection of short fiction with the generous support of the Canada Council for the Arts. She is an MFA candidate in the University of British Columbia’s creative writing program and lives in Hamilton with her partner and daughter.

Follow Jaclyn on Twitter @jaclyndesforges and on Instagram @jaclyndesforges