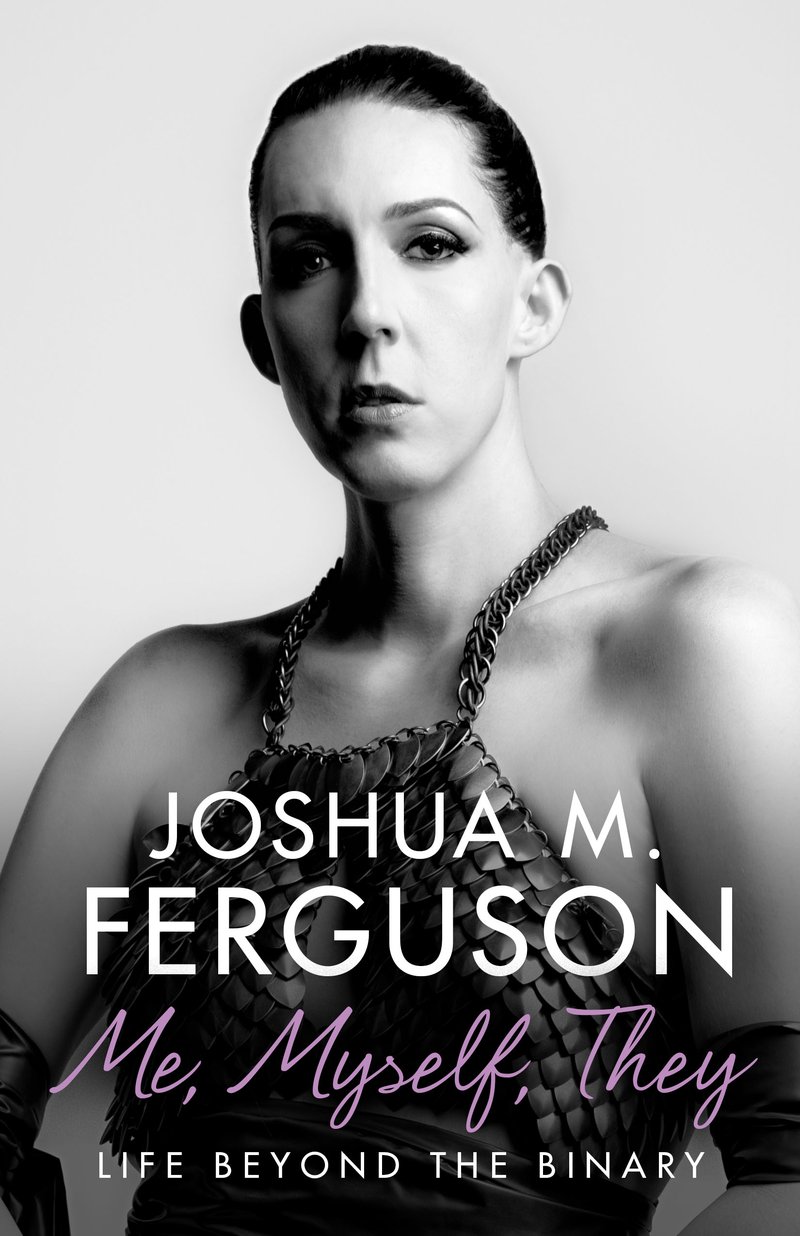

Casey Plett Reviews Joshua M. Ferguson’s Me, Myself, They: Life Beyond the Binary

Joshua M. Ferguson. Me, Myself, They: Life Beyond the Binary. House of Anansi. $22.95. 304 pp., ISBN: 9781487004774

Me, Myself, They: Life Beyond the Binary by Joshua M. Ferguson bills itself as a memoir, but this quick yet uneven read is more an interconnected book of personal essays. Ferguson, a non-binary trans person who grew up in small-town Ontario, survived bullying, violence, and depression to become a successful filmmaker and history-making activist (On May 7 of last year, Ferguson successfully received, after a long public fight, the first non-binary birth certificate in the province.)

Chapters in Me, Myself, They are explicitly divided by the experiences and personality traits of the book’s multi-faceted author, with titles like “The Survivor,” “The Alchemist,” “The Advocate,” “The Philosopher,” respectively focusing on violence, trauma, activism, and gender philosophy. This is in refreshing opposition to the linear timeline of many trans memoirs. The narrative moves backward and forward in time among adulthood, childhood, and adolescence, all building toward Ferguson’s messages of allowing for space beyond the two-gender binary, celebrating the beauty of any human who doesn’t fit into dominant gendered space (in fact, questioning the whole idea of dominant gendered space).

This chronology is successful—it’s as natural as listening to a friend on a long drive recount the harsh and beautiful tales of their life. In both structure and authorial drive, Me, Myself, They would find itself at home amongst other trans non-fiction works such as Kate Bornstein’s Gender Outlaw and fellow Canadian S. Bear Bergman’s The Nearest Exit May Be Behind You.

Unfortunately, the quality of the writing does not live up to the laudable aims of the book nor the compelling story present in the life of its author.

First, on a sentence-level, Ferguson’s prose feels unfinished. A representative example: They write of getting “madam’d” by strangers then “sir’d” once they speak: “People are literally mixed up by my presence in person because my gender expression does not register with what my voice or my forms of identification lead them to assume my gender is.” Mouthful sentences like these, ripe for a sharp-eyed editor to get in there and root around, abound throughout the text. As a whole, they make the book a sloppy read.

Second, the storytelling is marred by pervasive asides, usually to repeat hopes and ideas that have come before. Examples: In the intro, Ferguson writes that the “script” of two genders “fails people who do not fit neatly into the binary”; that “Our notions of gender are dependent on both culture and history”; and “our uniqueness can also be our sameness, and it can unite us.”

Certainly, these are all true statements in my book! However, the story consistently hits the brakes to repeat these ideas and others introduced early on, and eventually they take the form of truisms. Ferguson writes:

Each day, my gender presentation has to be carefully measured depending on who I’m seeing, where I’m going, and how I’m feeling. I wonder how far I can push my presentation and how much I can be myself. I wish that I could be who I am every single day, but it just isn’t possible. Isn’t that a sad thing? Perhaps I’m not so alone here. In fact, I know that I’m not. Perhaps you can’t always be who you are, either. I’m sure that’s the case for many people. As I’ve said, we are all more similar than we are different.

“I wish that I could be who I am every single day, but it just isn’t possible.” Now that’s a statement for an out trans person to make! It’s ripe for unpacking and insight into the complexities of life as a gender non-conforming person moving around in the world.

But already by paragraph’s end, we’ve pivoted to a vague universality, “Perhaps you can’t always be who you are, either,” and then to a vague truism, “We are all more similar than we are different,” a repetition of what we’ve heard since the beginning of the book.

I share most of Ferguson’s opinions and positions, and I’d be glad to think the larger world might hear them by the truckful. (Armed with the muscle of House of Anansi’s publicity department, I have no doubt said truckful will be delivered.) And as a binary trans woman, I came to the table eager to read an author carrying a mix of experiences both similar and differing from mine. But sitting alone in my apartment turning pages, I longed for a better written book.

Casey Plett wrote the novel Little Fish, the short story collection A Safe Girl to Love, and co-edited the anthology Meanwhile, Elsewhere: Science Fiction and Fantasy from Transgender Writers. She wrote a column on transitioning for McSweeney's Internet Tendency and her reviews and essays have appeared in The New York Times, Maclean's, The Walrus, and Plenitude, among others.