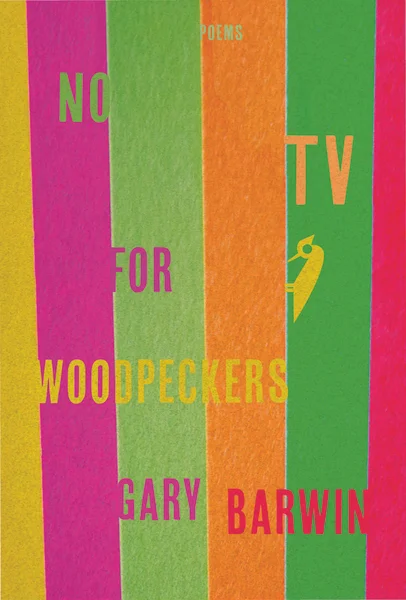

Gary Barwin. No TV for Woodpeckers. Wolsak and Wynn. $18.00, pp. 104, ISBN: 9781928088301

A Review of Gary Barwin's No TV for Woodpeckers

Review by Phillip Crymble

In the back matter of No TV for Woodpeckers, as a gesture of thanks to both his parents and children, Gary Barwin writes “‘we’re all barnacles on the rump of family,’ and that has taken the poems to better places.” Those familiar with Barwin’s back catalogue might recall that this somewhat puzzling nautical proverb was originally expressed by The Sea Pride’s master sailor in his Giller-nominated novel Yiddish for Pirates. Barwin’s decision to bury such an arcane metanarrative fragment deep within the paratextual ephemera of the collection is entirely consistent with his poetic practice, and in establishing an oblique connection between the two books, he invites us to entertain comparisons. Just how we’re meant to interpret this made-up old saw, never mind how we’re meant to read it against itself, is difficult to say. Barwin’s debt to the presence and efficacy of family in improving his poems, however, is disclosed in no uncertain terms.

Among the collection’s prefatory pages, Barwin includes an epigram by post-Language poet and fellow SUNY Buffalo alum Juliana Spahr: “We come into the world./We come into the world and there it is.” This spare account of inception introduces and releases the two discreet energies that compete for agency in the collection as it goes forward. The first of these concerns a welcoming and re-legitimizing of human receptivity (as evidenced in the more personal, family-themed poems), the second, how language, by its very nature, closes down and even undermines utopian possibilities of unmediated communication.

Our collective inability to accurately render the world as we experience it through language has troubled and preoccupied those dedicated to theory-driven poetries ever since Ferdinand de Saussure let the genie out the bottle over a hundred years ago, and Barwin, for the most part, writes out of this tradition. As No TV for Woodpeckers progresses extant texts are found, appropriated, redacted, erased, overwritten, and, as Barwin puts it, “re-populated.” Taxonomies, too, feature prominently in the collection, as everything from invasive species to assault weapons to keystroke symbols are catalogued and inventoried with such minimal editorializing that they seem auto-generated. That said, there are a number of poems where lyricism and affect are welcomed in, and these poems, in almost every instance, are themed around family or personal experience. “The Waltons, My Tooth, and the Oral Torah,” a tour de force, and one of the most moving poems in the book, is a case in point.

First and foremost, this poem is an elegy. That its closing gesture “Goodnight/Corabeth Walton whose real name was Ronnie Claire Edwards/on our 29th anniversary, you died in your sleep” bears a striking resemblance, in its weight and cadence, to “the war in Spain has ended long ago/Aunt Rose,” is telling. Aside from being one of Allen Ginsberg’s most heartfelt poems of personal loss, “To Aunt Rose” is also a poem that expresses great love and affection. Barwin’s poem, too, falls into this category, as there is a complex and remarkable conflation at work within it that directs the reader to forge an equivalency between the celebration of marital love and the death of the actress who played Corabeth Walton. Barwin’s speaker says of the family on which the 70s TV drama series was based: “There were moments of great tenderness/between the Waltons, though admittedly/also much woodcutting and sentimentality.” What the deadpan humour cleverly disguises here is the fact that in order to express authentic tenderness in poetry, we must consistently incorporate the mundane, and risk the sentimental, which is precisely what Barwin does throughout.

Method, and, in particular, the Oulipian N+7 method of noun substitution, is what underpins many of the poems in No TV for Woodpeckers, especially those in the opening section of the book. But when it comes to “The Waltons, My Tooth, and the Oral Torah,” the ‘mundane’ structural counterpoint to the affect and lyricism so present in the poem borrows more from “new sentence” protocols developed by originary Language poet Ron Silliman. Predicated on a recurring juxtaposition of non-sequiturs, Silliman’s new sentence approach was designed to undermine literary realism for political reasons, and like many of the Oulipian experiments, it, too, employs a static methodology. While Langpos, as a rule, tend to consider subject-centred poetry to be anathema to their practice, Lyn Hejinian, another of the movement’s founders, often marries Silliman’s closed system structural techniques to a poetry of confession rooted in real world experience. Most clearly evident in works like Oxata and My Life, Hejinian’s fusion of avant-garde and official verse culture traditions pioneered the kind of hybrid sensibility Barwin reproduces in “The Waltons, My Tooth, and the Oral Torah.”

Those who have read No TV for Woodpeckers attentively will also be rewarded by the poem’s self-reflexive qualities as “The Waltons, My Tooth, and the Oral Torah” contains strategically placed references to the themes and concerns that preoccupy the collection as a whole. Wider fixations on naturalism, technology, and the primacy of master narratives are all distilled here, as are the anxieties associated with dental surgery and foreign travel encountered earlier in the book in “Travelling in Peru without my Glasses.” And that the poem is rife with “real time” email interruptions and authorial asides, contains a deliberately introduced numerical calculation error, and repeatedly draws attention to the fact that it is a made thing, renders it as post-modern as it is post-avant.

But all of these redirects and sleights-of-hand aside, the “real tenderness” that cannot be elided here asserts itself in what appears to be an unironic human longing for the kind of pure and unmediated communication the Oral Torah represents. Again and again, Barwin shows us how charlatans, business interests, and technology come together to create cultural texts and interfaces that jam, compromise and contaminate our abilities to forge meaningful relationships with one another. But by worrying “the empty spot” left by Ronnie Claire Edwards’ death in the same way the speaker imagines his tongue will continually return to probe the socket of his soon to be extracted tooth, something transformative takes place. What Barwin commemorates in “The Waltons, My Tooth, and the Oral Torah,” what he elegizes, is the elegiac mode itself, and by demonstrating what language can do, he allows us to feel, if only briefly, less lost, less lonely, and less alone.

Phillip Crymble received his MFA from the University of Michigan and now lives in Fredericton, New Brunswick, where he divides his time between pursuing a PhD in Literature at UNB and serving as a Poetry Editor for The Fiddlehead. In 2016, Not Even Laughter, his first full length collection, was nominated for both a New Brunswick Book Award and the J.M. Abraham Prize.