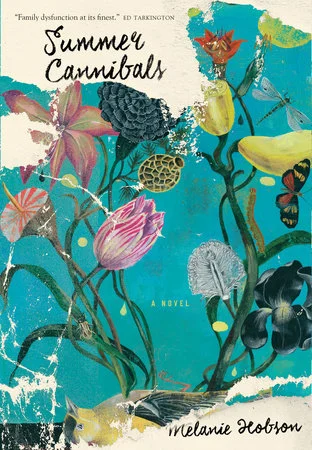

Melanie Hobson. Summer Cannibals. Penguin Canada. $24.95, 288 pp., ISBN: 978-0670068357

A Review of Melanie Hobson’s Summer Cannibals

Review by Jessica Rose

Stately homes that shelter family secrets have long been familiar in literature. With creaky floorboards and winding corridors, some dwellings become characters with personalities independent of their inhabitants. However, when thinking of such settings, one might think first of Misselthwaite Manor or Jay Gatsby’s West Egg mansion. Less often we think of a home in our very own city.

Perched atop the Niagara escarpment and weathered by years of neglect, the three-storey home in Melanie Hobson’s debut novel, Summer Cannibals, has three floors, two staircases, seven bedrooms, a coach house, a library, a butler’s pantry, and many secrets. While David and Margaret Blackford, the husband and wife who live inside the house, are fictional, the house itself is not — it is created in the likeness “with a few embellishments” of Hobson’s childhood home on Hamilton’s mountain brow.

It’s to this Georgian-style mansion, owned by the Blackford family for more than 30 years, that David and Margaret’s three adult daughters — Georgina (known as George), Jacqueline (Jax), and Philippa (Pippa) — are summoned. Pippa, the youngest, is pregnant with her fifth child, having left her husband and children behind in New Zealand. She is unwell, and her sisters plan to tend to her, but very quickly, readers discover that Pippa isn’t the only Blackford sister desperate for an escape. The result is a dark, twisted tale of long-buried secrets, unquenchable lust, vengeance, and greed.

In Summer Cannibals, each self-centred member of the Blackford family is more awful than the next, with the exception of David, the most arrogant and unpleasant of them all, with his contorted sense of reality and his unrelenting ego convincing him of his superiority. “David likened himself to a duke who’d made a pile of money that would become, with his eventual passing, Old Money, which could be used to maintain The Estate,” writes Hobson. Prone to childish tantrums, David thrives on controlling others, which includes the rape of his wife. At times, Hobson seems to almost romanticize his violence. “The violence was a periodic necessity of their life together, like a climate oscillation — a prolonged freeze hit by a sudden thaw,” she writes.

Without exception, every character in Summer Cannibals is weighed down by the life he or she might have led. Some of the book’s many subplots include Pippa’s interest in polyamory, Jax’s eagerness to meet an ex she hasn’t seen in twenty years, and Margaret’s failed career as an artist. While the first half of Summer Cannibals is steadily paced, the plot becomes more haphazard as it progresses. The book feels crowded with so many problems existing under one roof. Hobson’s seeming attempts to be scandalous and seductive instead read mostly as melodramatic.

Summer Cannibals, at times, feels slapsticky, during rare moments when Hobson infuses comedy into the plot. This is especially true when David hosts a garden tour for tourists that ends in chaos. However, despite the book’s shortcomings, what makes it a worthy read is Hobson’s stunning prose. “Dew was holding the petals down and making leaves droop, and each blade of grass, as the weak sunbeams hit them, looked beaten,” she writes in one of the book’s many metaphorical phrases. With an ability to make readers feel as if they’re inhabiting the Blackford mansion and its surrounding gardens, Hobson creates a world that is difficult to look away from — even if the characters inside can be exhausting.