A Living Portrait of a World: In Conversation with Steven Price

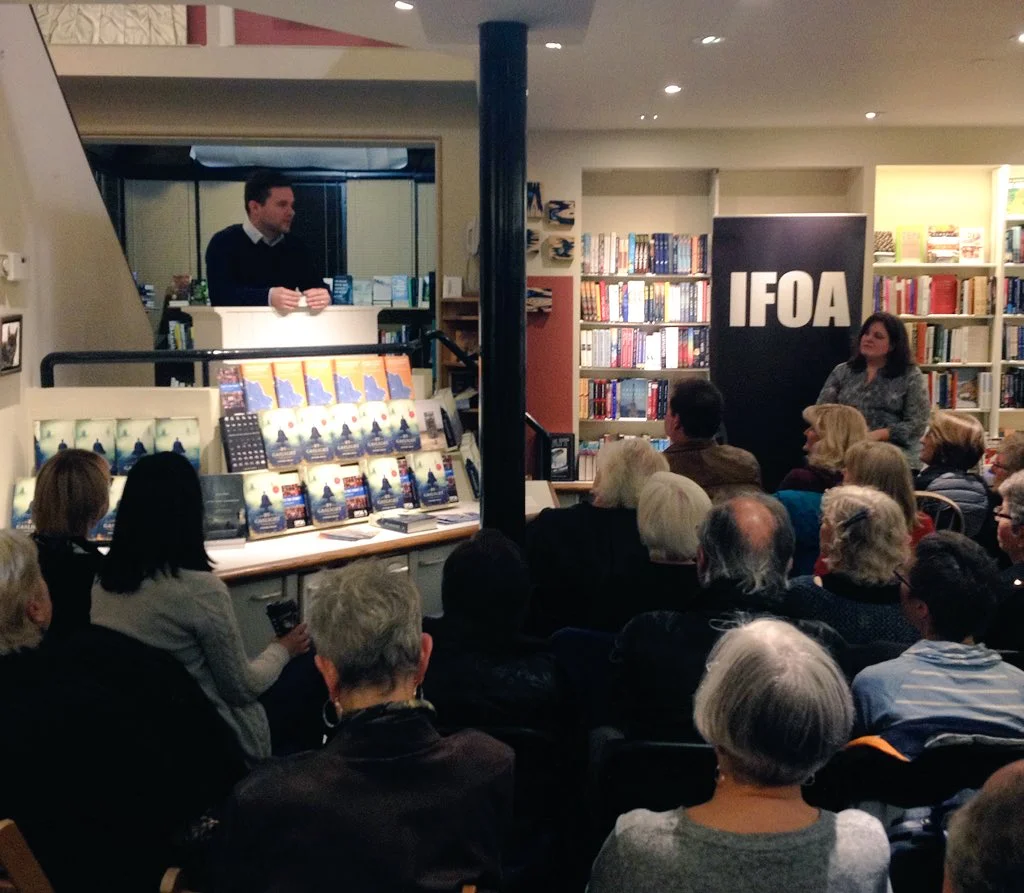

On the evening of Tuesday October 25, 2016, the IFOA's Lit On Tour organizers brought writer and poet Steven Price to A Different Drummer Books in Burlington, Ontario. In front of a large audience of admiring readers, Steven read from his critically acclaimed new novel, By Gaslight, and generously shared his thoughts about the book, his family history, and his important friendship with late editor Ellen Seligman. What follows is a condensed and edited version of our conversation.

Steven Price. By Gaslight . McClelland & Stewart. $36.00, 752 pp., ISBN: 9780771069239

Dana Hansen: I want to start by asking you about why you chose this particular location and time period for By Gaslight. Your first novel Into That Darkness was set in contemporary Victoria, B.C. during the aftermath of a horrific earthquake. Your new novel takes place in 1885 in Victorian London, and has a similarly dark kind of atmosphere. What drew you to write about this time and place?

Steven Price: Actually, the novel started with the character of Wiliam Pinkerton, and grew from there. Pinkerton was a real person, and so I found myself locked into the era of his life. He led me to his time and place, I guess. In truth I knew very little about the Victorian world when I started writing.

DH: The reviews of By Gaslight have all been really positive. Many readers have clearly enjoyed the book. I thought one particular reviewer’s comment from The National Post was really interesting. He said, By Gaslight is “not a mystery as we understand the genre, but it is a novel of mysteries closely held and destructive.” Do you feel that that is a fair description of the book?

SP: I think it's a lovely description, and I hope there's some truth to it. I imagine every author is surprised by some of the responses to their books. Which is as it should be. You have a certain idea of something that you’re moving towards when you’re writing, but it's a gradual movement, and a slow one. For the reader, to read from page eighty to page ninety might take fifteen or twenty minutes. For the writer, it might have taken thirty days to cross that distance. So what you’re experiencing as the writer is very different from what the reader experiences, because the experience of time is so profoundly different.

DH: I read that the initial spark for the story came from your own personal history, from a story about your great-grandfather Albert Price.

SP: Who has a cameo in the book.

DH: He has a cameo, yes, as the gunsmith’s apprentice. Can you tell us a little bit about Albert’s story and how that got you thinking about writing this book?

SP: Some books have a wonderful origin story, but mine didn’t emerge from any particular event. I found myself wondering at a certain point: I just wrote a 731-page novel about Victorian England. Why did I write it? What was I thinking? The novel began with its opening paragraph - an unusual way for me to enter a book - and that paragraph is really just a character sketch of the detective William Pinkerton. I'd read a biography of Pinkerton some years earlier, in which he was described as a man who got along better with criminals than he did with law enforcement officials. He had very little respect for other private detectives - his father excepted of course - and he had very little respect for police officers, because there was so much corruption in the 19th century. But he got along really well with criminals. He found there was this kind of moral code, honour among thieves, with the criminals that he really respected. He would go down, in his off hours, to the underworld bars in Chicago and he would buy drinks for the crooks, and the crooks would buy him drinks, and they would drink together and talk, and then he’d go home and go to sleep with his wife, wake up, say hello to his daughters, go off to work for that day and try to catch the men he was just drinking with the night before. And he usually did; he was very good at his job.

Now of course, there was always a professional reason to hang out with these guys and be friendly with them, because he might get a little bit of information; the criminals were competitive with each other, maybe they would give him a tip, but he also just liked the company. And he would put these men behind bars, and they would go to jail for ten or fifteen years. And when they got out of jail, they would come see him and he would give them money and write them letters of introduction so they could get a job. He would try to help reform them because he had compassion for these people and he liked them, which I thought was really interesting. He had all the qualities and traits of a master criminal. He was big and violent and the ends justified the means for him, so he would do whatever he had to do.

Regarding my family story, on my father’s side, the Prices came over in 1890 to Victoria, B.C., from London, England. Albert Price, my great-grandfather, was a young man in 1890 who was trained as a gunsmith in London, and he crossed the Atlantic – a considerable journey in 1890 – then booked passage on the new railroad, all the way to the west coast of Canada. And from Vancouver he sailed further west, again, to Vancouver Island, and then when there was only ocean ahead of him, he stopped. Why did he do that? Why did he make that journey? He had no family there, no friends, he knew nothing about the place.

My grandfather passed away in the late 1990s and about fifteen years ago his younger brother, a recluse named Bud, came down from the property where he had been living, on a mountain, up island. I met with him for an afternoon and he was this raconteur, he started telling these wonderful stories.

And one of the stories he told was about how Albert Price had emigrated to Victoria, and used his gunsmith skills to set up a lock and safe shop, a locksmithing shop, still in the family today. Apparently, Albert was fleeing the law when he left London. He got in some terrible trouble with the law, and he was running. He was a fugitive.

There was a link there, I think, between this story of my great-grandfather - a man who had flirted with the wrong side of the law, before establishing a business protecting people's property - and that depiction of William Pinkerton, as a detective who felt such a great kinship to the criminal class. But it was a subconscious connection, not something I sought out. It surprised me.

DH: Despite the fact that you included a number of characters that really did live (such as the Pinkertons), you state in your author’s note in the book that this is not a historically accurate portrayal of London in the 19th century, and that it is obviously fiction and not a history book. But you clearly did a lot of research for this book; there are just so many exquisitely fine details of the period. I wonder if you could tell us what the research process was like in writing this novel.

SP: Thank you. I regret many things I’ve written, but rarely have I regretted anything as much as I’ve regretted writing that author’s note.

DH: And I bring it up, of course.

SP: You know, I wrote that because – and I have no problem with other books that do this – but I was feeling impatient with having to cite sources, as if By Gaslight were an academic work. I wanted to create a space for dreaming again. I wanted a living portrait of a world. I didn’t mean to suggest that I had done no research at all. I worked very hard to keep things true, especially the parts of the book that have to do with people who really lived; I wanted to keep everything as accurate as I possibly could. But I didn’t want to cite the fifteen pages of sources that I would have had to cite if I did that. So I thought I would make this very obvious point and say, “Hey, everybody, this is fiction!” Well, some reviewers seemed to have taken that to mean I didn’t do any research at all and just made it all up.

DH: You did research.

SP: Yes. Absolutely. I read many books, as many books as I could. The Victorian era is so interesting because it’s the first period in history that has been thoroughly documented. There was journalism, there was the dawn of photography, and there was the incredible rise in literacy. So there’s no end of sources that you can consult, and it’s a wonderful thing for a writer, but it’s also a great hazard because there are many other people who have read other books and there are many experts out there on this era. I worked hard because I wanted to make sure that it was very accurate, and sometimes that would lead me to surprising details, details that perhaps weren’t really well known. Then I would find myself thinking, Do I include that detail, even though it might be poking the bear and people will say that’s not true? Well, it is true, it’s just not well known. Or do I go with the more traditional stereotypical portrayal of the era? I always went with what I thought was factually accurate.

While I didn’t get to travel to any of the places specifically for the book, because I have young kids at home, most of the places that I’ve written about in the novel, I’ve either lived in or travelled through already, such as South Africa. I’ve been to London several times, and I lived in Virginia. So what I was doing was calling upon my own memories to imagine these places. And there's a kind of freedom in that.

DH: William Pinkerton and Adam Foole, two of the main characters in By Gaslight, become quickly drawn into each other’s acquaintance. We’re not going to give anything away about what happens, but we discover that there are deeper connections between them. There’s a kind of Jekyll and Hyde dynamic with these two characters, and a lot of play with ideas of good and bad, right and wrong, light and dark. I get a sense from your first novel and your poetry that these may be themes you’ve explored before. Is it important for you to investigate this idea of whether someone can be wholly good or wholly bad? Pinkerton, for instance, is on the right side of the law, but may have a darker side. And the opposite for Foole: he’s a thief, but there seems to be a softer, better side to him, too.

SP: I like the Jekyll and Hyde comparison. There are three main characters of course – Pinkerton, Foole, and Shade. But Pinkerton and Foole are the ones that we follow through the book in alternating chapters. I set out to create Foole as a kind of foil for Pinkerton, so where Pinkerton is a character for whom the ends justify the means, for Adam Foole they don’t. Whereas Pinkerton is a person soaked in violence, Foole is somebody who has no patience for violence, no interest in violence, and doesn’t use that in his work. I set out to create these two very distinct characters who were playing off of each other, and yet as the novel proceeded – and books sometimes write themselves as much as we write them, and often the act of writing is an act of listening, where you’re trying to listen to what the book is saying back to you and what it wants in the connections its making, and you’re trying to listen to that and let the book figure out what it wants to do, which sounds a little crazy, but it is a little crazy – as the book proceeded, that distinct quality between the two characters started to blur as if the characters were contaminating each other, which I thought was kind of an interesting thing.

But of course that’s what life is like, and that’s what people are like. You can be very clear-cut in who you are until you find yourself pushed into a situation that is somehow morally compromising or complex. There is a wonderful line from the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz. Miłosz survived the Nazi occupation in Poland and fled from the Russians. Sitting at a café in Paris watching all these people walking past him on the street, he wrote a poem. He looked at these people and thought, innocence - that is what you have before you are subjected to a test. In other words, whether you fail the test or you pass the test, whether you do the right thing or the wrong thing, you no longer are innocent. I feel like that’s sort of what is happening with the characters across the course of this book. They’re constantly being compromised by impossible situations, constantly having to make choices. No matter what they do, they can’t ever go back to who they were before.

DH: Could you talk a little bit about the significance of the father-son relationships in the novel?

SP: The first thing I wrote was the opening paragraph of the novel. It ends with “The only man that William Pinkerton ever feared was his father.” I don’t think there would be a book if I hadn’t got to that last sentence. It’s kind of a strange thing to say, but books grow out of characters, I think, in conflict, that is, characters who are faced with something that throws up a reflection of themselves, That last sentence is the moment William Pinkerton is suddenly in conflict. His father has recently died, and he has to deal with his grief. When I say grief I mean his long memory of who his father was, and who his father is. The two things aren’t the same. In William Pinkerton’s case, I think of the entire book as a love story between him and his father, as he tries to become someone no longer dependent on his father. He’s no longer the child; he can become the parent of his own children.

Foole’s backstory is revealed in the fifth section of the book, right in the middle: where he comes from, which are very modest circumstances, the adventures he had as a very young boy orphaned in the world. For Foole, one of the important parts of his life has been this idea of identity and belonging. There’s the family that you’re born into and the family that you make, and for Foole he never really knew the family that he was born into, so for his whole life it’s been about the family that he’s made. He had a moment in his life where it seemed like it wasn’t a question of choice, as though he’d found a family that wasn’t just of his choosing, and he’s always wanted to go back to that place, but he’s also always felt a betrayal because that was taken from him by force. That’s the source of his anguish, I think, as a character.

DH: Foole goes on to develop this very odd family of his own, which produces two extremely interesting characters, Molly and Fludd. They become the most unlikely trio you can imagine. Can you tell us a little bit about Molly and Fludd?

SP: Molly is a young girl. She is a pickpocket, an orphan raised in the streets of London. She was virtually owned as a young girl and Foole buys her and then gives her her freedom. But she’s not a child – well, she is a child, absolutely she's a child, but she’s not a child as we would think of it today, here, in Canada. She has a degree of street smarts that elevates her so that she is a part of Foole’s team, a working member. It’s a complicated relationship because of course he looks at her as a child; it’s almost as if she’s his adopted daughter, but at the same time he relies on her as a professional part of his crew. And then there’s Japheth Fludd, who is a very large man, bearded, tattooed, very rough looking. He’s been in jail and he’s recently come out of jail. These three people form a kind of family.

DH: You are an acclaimed poet with two collections of poetry. I’m wondering if you’re still writing poetry, and how poetry might inform your novel writing.

SP: I haven’t given up poetry. I’m not currently writing it. I can’t do both at the same time. I think you think differently when you write poetry. But I’m looking forward to the day I can go back and write some more poems. How do the two inform each other? I came to writing first as a poet and I published first as a poet, and I still describe myself as a poet, but I think the two are fundamentally different, very different. Poetry is closer to non-fiction. The vehicle for fiction, the kind of fiction I write and the way I think of it, is the character. So your characters are moving through time and through space, and that’s what the story is, whereas in poetry it’s a very different experience. You can write a poem about a landscape, you can write a poem about a person, you can write narrative poetry, there’s a lot of different kinds of poetry, but fundamentally what it’s moving towards or seeking is some truth about the world, some observable wisdom or an attempt at wisdom, which is a little bit closer, I think, to nonfiction. In other words, the poet can step back and speak about the poem as a whole, whereas in fiction everything is carried along by the characters.

DH: Did the transition from poetry to fiction come easily for you?

SP: Well, I’ve always done both. Even though I published first as a poet and I went to grad school for poetry, the transition wasn’t difficult.

DH: You’ve written about the experience of working with the iconic McClelland & Stewart editor, Ellen Seligman. You wrote a beautiful tribute to her in the Literary Review of Canada, in which you describe what became a year-long process working on this book with her. You said that you cut 35,000 words from the novel, that you added some 70,000. You removed two significant characters, and you rewrote the ending. Could you talk a little bit about your time working with Ellen, and what the importance is of a good editor to a book like yours?

SP: Ellen Seligman edited many of the novels we have come to think of as the Canadian canon. She edited and published many of the most accomplished writers in the country and became dear friends with them, writers like Michael Ondaatje, Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, Jane Urquhart. She kept an eye out for young writers as well, ones she could encourage. She would get in touch with young writers and write them letters encouraging them about books that she’d seen of theirs even if she wasn’t going to publish them. It was her way of saying, “Keep going at this, this thing is important, these words matter.” And that was how she lived her life – words mattered to her.

We worked on By Gaslight for thirteen months. I didn’t know her before I signed with her. So this was our first book and of course my last book with her. She had a very strange way of working on a novel. Usually editors will mark up a manuscript, send it to the author, the author will receive it, and start trying to wrestle with the edits. She liked to edit in real time, on the phone, and so we would have these long intense conversations. The phone calls would last five to six hours, often five days a week, week after week. It was the most generous, most extraordinarily complimentary act that a writer could experience, that somebody would be so engaged in their work and feel like it mattered so much that they were working that hard at it.

I think sometimes there might be a misconception about what editors do. Some people think that editors get a book in front of them and then they fix it. That’s not really what they do. It’s certainly not what Ellen did. I suppose there might be editors out there who force themselves onto a manuscript, who try to change a manuscript to suit their tastes, but Ellen wasn’t like that. Ellen would read a manuscript, get a sense of what it wanted to be, what it was trying to be, because a book has its own internal logic. It has its own questions that are raised at the front end of a book, that maybe should be coming down at the back end of a book or have been dropped somewhere along the way. An editor’s job is to look at that, figure out what the book is trying to do, and then try to bring that to the writer’s attention and ask questions.

Ellen asked a lot of questions. Ellen liked to ask questions on a macroscopic level, big questions, overall questions about the book, about its ideas or its themes or what it was trying to do, and on the microscopic level. She began at the beginning, and she worked through a manuscript in a linear fashion, which is a little unusual. We dealt with what was on page one, and when we got that working we dealt with page two, and when we got that working we dealt with page three. Many times there would be a point at which we’d be faced with a sentence, and I’d be trying to figure out a solution to it because she would never give me the solutions, and she would sit there quietly on the end of the phone while I typed and I worked and reworked and I found the sentence.

So it was a very intimate process and what happened across these thirteen months was she became an intimate…I want to say friend, but it was more than being a friend. She was this intimate companion in this creative experience, this journey that we were on. Which was really wonderful, but she was always only ever a voice on the end of the line. I never got to meet her in person. I travelled out to Toronto to see her; we had set up a week to meet, have dinner, and this was in November, and she died the following March. Three weeks before she passed away, she phoned me up – we’d kind of put the book almost to bed by then. She phoned me up one day and said, “I just wanted to hear your voice.” That’s not like Ellen. Ellen always had a reason to call. We had this lovely little fast chat. She was calling to say goodbye, I realize now. Three weeks later she passed away. But I always wished I had had a chance to meet her, give her a hug, tell her how much she meant to me, what an important woman she was in my life.

DH: So what’s next for you? Are you working on something now?

SP: Well, I get home on Thursday, and I get to see my kids and my wife. I think I’m going to sleep for a little bit, and then I’ll see.

DH: Thank you so much, Steven.