When Things Start to Fall Apart:

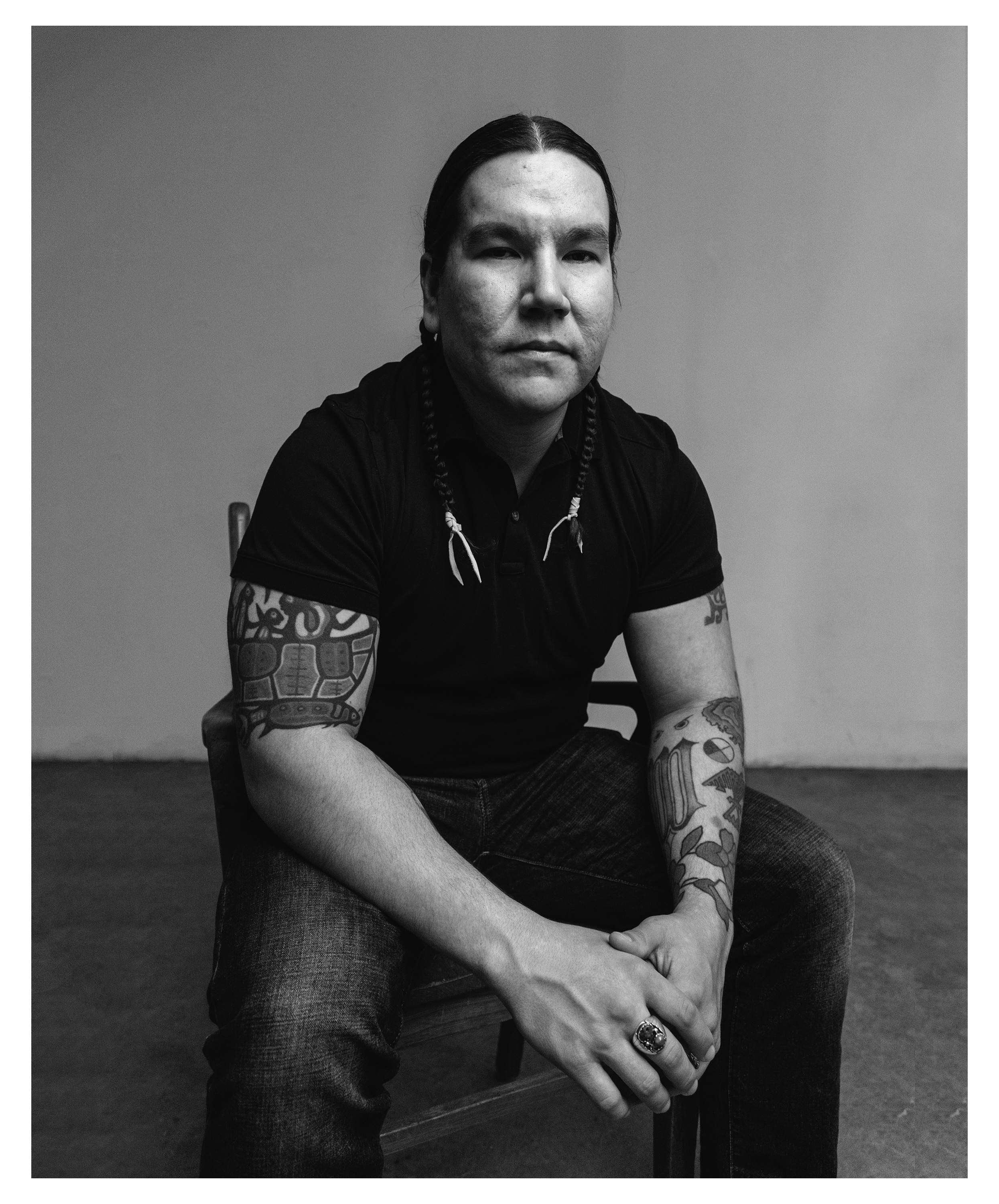

Andrew Wilmot In Conversation with Waubgeshig Rice

Photo credit: Rey Martin

Waubgeshig Rice is an author and journalist originally from Wasauksing First Nation. His first short story collection, Midnight Sweatlodge, was inspired by his experiences growing up in an Anishinaabe community, and won an Independent Publishers Book Award in 2012. His debut novel, Legacy, followed in 2014. He currently works as a multi-platform journalist for CBC in Sudbury. In 2014, he received the Anishinabek Nation’s Debwewin Citation for excellence in First Nation Storytelling. Waubgeshig now splits his time between Sudbury and Wasauksing.

Waubgeshig Rice. Moon of the Crusted Snow. ECW Press. $17.95, 224 pp., ISBN: 9781770414006

Andrew Wilmot: Hi, Waub! Thanks so much for agreeing to speak with me about your new book, Moon of the Crusted Snow, and congratulations on its publication. I’d love to ask you about the genesis of this story. When did it first start taking shape for you?

Waubgeshig Rice: Hi Andrew! It’s my pleasure and honour to discuss my new book with you. Thank you very much for this opportunity, and for your kind words. The story that eventually became Moon of the Crusted Snow really started taking shape about ten years ago. I’ve always enjoyed post-apocalyptic or dystopian fiction, but it wasn’t until I read The Road by Cormac McCarthy that I really wanted to explore writing my own story in that genre. I really enjoyed that novel, but it left me wishing for more stories like it from an Indigenous perspective. I felt that because Indigenous nations have already endured apocalypse and largely exist in relative dystopia, a book about the end of the world that’s centred on an Indigenous community would reflect a different spirit. It was an idea I kicked around for a long time, before finally sitting down to write it more than three years ago.

AW: Your previous books, Legacy and Midnight Sweatlodge, both dealt with different forms of isolation experienced in First Nations communities via, among other things, location, privilege, and identity. In Moon, though, nature itself is a kind of accelerant, with an extreme (and possibly apocalyptic) winter furthering this sense of isolation and facilitating conflict. What led you to want to test this group of people in this way?

WR: I think winter has always been the ultimate test of survival for humankind. Since time immemorial, people who’ve lived in climates that bring winter have always had this looming season of great challenges. Many cultures and nations would prepare for months to ensure communities made it through to spring. But that’s something we’ve largely forgotten, with the luxuries of modern infrastructure. The community in Moon of the Crusted Snow isn’t that far removed from the days of hunkering down for the winter. But in just a couple of generations, a lot of people have moved away from winter preparations like hunting and gathering wood, and have become more reliant on the amenities that bring them closer to the world to the south. So when they lose many of these conveniences, it’s a sobering wake-up call to re-examine their roles and responsibilities to the land and their community as Anishinaabeg.

AW: Piggybacking on all this talk of isolation, the book wastes no time in establishing the stakes: no cell service, no landlines, no outside communication of any kind as winter very quickly sets in. All told, it’s an excellent horror set-up. When laying the groundwork for this story, did you have the sense that you were writing to a specific genre? Or do you see this book as carving its own path?

WR: Because I was inspired by the post-apocalyptic genre in general, I always saw this story as part of those discussions. I wanted it to complement stories like The Road by showing how an Indigenous community would respond to a crisis that “ends” a world and survives in its aftermath. It’s not a unique or original concept at all—see The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline and Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich, for example—but I think there’s an opportunity for richer conversations about the sustainability of communities and what we can learn from the land itself when things start to fall apart. It wasn’t until editor Susan Renouf and I were into the revisions that we realized the story could serve as a decent thriller, too. As we worked to build the tension in the community, I think we started to scare ourselves!

AW: Speaking of paths and following them (or not), Evan Whitesky is an interesting protagonist in that despite being a “rez lifer” he seems to exist on the fence between two worlds—he’s part of the community, yes, but not fluent in Ojibwe and still learning and growing comfortable with older Anishinaabe customs. What was your reasoning behind this?

WR: I appreciate that observation, because it really gets at what I was trying to do with him in general. I wanted to portray Evan as a rez “everyman” who embodies the paradox of modern Indigenous life, like many of us who grew up in a First Nation do. Within just a couple of generations, culture and language are scrubbed from his community due to the brutal impacts of colonialism. Even though he didn’t endure the violence of residential schools himself, because his grandparents did, very little of his Anishinaabe identity was passed down to him. It’s the common intergenerational trauma of these terrible assimilative measures. Fortunately, he still has links to the old ways, and they become clearer and more important during this crisis. But basically, I wanted to convey that there are a lot of people like Evan, wanting to learn about being Anishinaabe but finding it hard to connect with those old ways even though they live immersed in an Indigenous community.

AW: As the community’s situation worsens, we’re given snippets of what things are like outside the community, War of the Worlds-style: bits and pieces of information doled out as rumour and hearsay. In the end, we never learn the true extent of things or the lasting impact of this especially brutal winter on the outside world—the word “apocalypse” being used in only one situation, and not until three-quarters of the way through the narrative. Can you speak to the decision to keep the story so laser-focused in this way? Was there ever a version of this story that focused more on the broader world?

WR: I only ever wanted to tell this story from the perspective of the people in the community. It was really important to me to give the Anishinaabe characters the primary voice because I wanted to highlight their sense of community and relationship with the land as a means to survive. That said, though, I did thoroughly imagine what happened that led to the blackout and its wider impact on the broader world as I was developing the story. Those details were part of my initial notes, but never made it into the manuscript. I had to run these parallel experiences of this apocalyptic event in my mind in order to effectively peel back the curtain on the southern, urban world both here and there. As things slowly crumble on the rez, they’re rapidly descending into chaos in the city. Honestly, it was fun to dip into that chaos throughout the story in different ways.

AW: Continuing to focus on the crisis at the heart of this book, I’d like to now dive into the Justin Scott character, as there’s quite a lot here to unpack. First, let me say that Scott is a fantastic villain—detestable in every way, especially in how familiar he is: an imposing, broadly sculpted white male with an aggressive, authoritarian streak who inserts himself into every situation, whether he belongs or not. What did you use as your starting point in developing a character like Scott? And was he always a factor in the planning of this book, or were there earlier drafts that focused more on just the survival/nature aspects of the narrative?

WR: I really like “detestable in every way”! That’s how I hoped readers would react to Justin Scott. Basically, I wanted to write as detestable a character as possible. An outsider coming in to manipulate and exploit the community was always critical to the plot. I wanted to create an antagonist who was essentially an allegory for settler colonialism on this land. I tried to make his physical and personal traits as alien as possible from the perspective of the Anishinaabeg in the story. He was there from the beginning, although a few months into writing the manuscript, I started to have some doubts. In this situation, would someone really leave a city and seek refuge in a faraway reserve? It seemed believable to me, but I worried it wouldn’t be to some readers. Then I went to a Halloween party in Ottawa and got to chatting with a dude there about the apocalypse (it was obviously top of mind for me back then, haha). He eventually revealed that his plan for an urban collapse was to find the nearest rez and survive there. That was all the validation I needed! Also, how presumptuous that he’d just expect to be welcomed to live there. And thus, Justin Scott became much clearer.

AW: Scott’s very presence, from his first moments, is both authoritarian and deceitful. It feels intentional that his first words, “I come in peace,” are followed by laughter—it comes across as mocking in its intent, approaching a community as one would an alien in a science fiction film. Following this, Scott proclaims himself a “man of the land,” implying that he doesn’t have anything to learn and aims to control both the response to him and his placement in the community, right from the jump. When first introducing this character, what aspects of him were important for you to immediately convey to readers?

WR: I think it was important for me to convey that he embodies conflict. He arrives well prepared and apparently very resourceful, but his intentions aren’t that clear. The community leadership is immediately in a bind due to his presence, and he’s able to take advantage of their uncertainty from the beginning. He inserts himself into as many situations as possible to flex his muscle and slowly assert control. At the same time, he earns the trust of some community members by exploiting their weaknesses. And I wanted him to be mysterious from the get-go as well. We never really find out anything about him, other than the skills and demeanour he displays as he settles in. What’s his story? It’s never made clear. I think that adds to the intrigue and loathing around him.

AW: While not an overly violent book by any stretch, there are certainly notes of action and violence throughout. However, much of it is both sudden and muted, without excess gore, drama, or deliberate stylization. It really fits the story and the relatively quiet setting. Is this your normal approach to writing violence, or did you set out to write this specific story in this way?

WR: Writing violence in a story about apocalyptic crisis is pretty much unavoidable. It was necessary to this story. But yeah, making those violent moments silent and muted, as you say, was very deliberate. That’s mostly due to the overall pacing of the book—it’s short, and while the descent into disorder is slow, the violence occurs as the tension builds and the rest of the story really picks up. So those moments had to happen quickly, and because it’s about survival, the characters had to move on. I’m not sure if it’s my normal approach to writing violence—I think it depends on the scenario.

AW: Throughout the book, concepts of death and rebirth are prevalent—of one society crumbling and another asserting itself, preparing to take the place of the former. In this case, it’s the idea that modern society (and specifically modern Canadian society) has failed and that survival depends on reconnecting with and reestablishing older customs. Was this something you’d planned from the beginning, or did this idea develop naturally through the writing of the book?

WR: This is a message that I had wanted to convey from the beginning. Part of it goes back to what I mentioned earlier about putting a different lens on post-apocalyptic experiences and why an Indigenous perspective is crucial to consider. Nations and cultures have survived since time immemorial on this land without the fragile luxuries we’re so dependent on today. If and when those things disappear, the answer to survival will be in the land, as it has always been. Also, a personal reason for driving this message home was to remind myself to reconnect with the land. I grew up on the rez with lots of land-based knowledge, but I’ve lost a lot of that since I’ve lived in cities for two decades now. So now it’s time for me to walk the talk, haha!

AW: What are you reading right now? What have you read recently that you’d like to highlight?

WR: This past year I read some of the most mind-blowing Indigenous literature I’ve ever laid my eyes upon: Tommy Orange’s There There, Terese Marie Mailhot’s Heart Berries, Eden Robinson’s Trickster Drift, and so much more. I’m finally getting around to reading Joshua Whitehead’s Jonny Appleseed, and next is Claudia Dey’s Heartbreaker.

AW: Lastly, what’s next for you in terms of your writing?

WR: I have almost a book’s worth of short stories done. I just need to polish up a couple more, and hopefully there’ll be a decent collection there. And I’m working on a non-fiction project with my current publisher, ECW Press. Details to be announced!

Photo credit: Jaime Patterson, Hidden Exposure Photography

Andrew Wilmot is a writer and editor based out of Toronto, Ontario. He has won awards for screenwriting and short fiction, with credits including Found Press, The Singularity, Glittership, Turn to Ash, Augur, and the anthologies Those Who Makes Us: Canadian Creature, Myth, and Monster Stories and Restless: An Anthology of Ghost Stories, Dark Fantasy, and Creepy Tales. As an editor, he’s worked with Drawn & Quarterly, ChiZine Publications, Broken River Books, ARP Books, Freehand Books, Playwrights Canada Press, Wolsak & Wynn, and is the former Marketing and Production Coordinator for NeWest Press. He is also Co-Publisher and Co-EIC, alongside editors Michael Matheson and Chinelo Onwualu, of the online magazine Anathema: Spec from the Margins. His first novel, The Death Scene Artist, was released in Fall 2018 by Buckrider Books, an imprint of Wolsak & Wynn. Find him online at: andrewwilmot.ca, anathemaspec.tumblr.com, and on Twitter, hating everything about Twitter, @AGAWilmot.